|

by Jim Watson

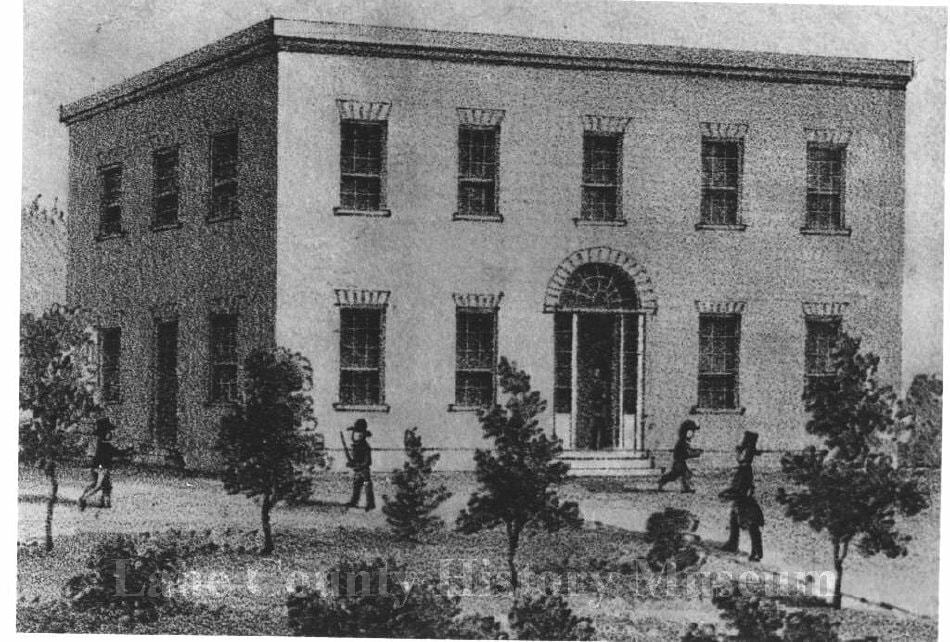

A century ago Eugene's Mercy Hospital was located on College Hill (see blog post "Eugene General/Mercy Hospital"). To connect the closest College Crest trolley stop on Willamette Street to the hospital, stairs were constructed in 1910. Though both the hospital and the trolley disappeared in the mid-1920s, the stairs remain across Willamette Street from Civic Park. The stairs, perhaps the last of their kind, connected to one of Eugene’s trolley routes that was part of a streetcar system that was once described as the greatest for a small city in the United States. The pioneer railway is remembered for having employed Wiley Griffon, Oregon’s first black trolley operator. Gwynne McLaughlin spearheaded a project to paint a mural on the stairs to honor their history while preventing the graffiti that has plagued them. Muralist Ila Rose painted the mural in May of 2019. Questions? Interest in helping keep the mural in good shape? Please contact Jim at [email protected]. Black and White Images Property of Lane County History Museum. Used by Permission. Historical information compliments of Andrew Fisher. Before UO and before OSU, there was Columbia College. Opened November 3rd, 1856 by the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, Columbia was the first college in Lane County, only the fourth in the Oregon territory. Enoch Pratt Henderson, a minister, was hired to serve as president of the college. The first student body consisted of 52 students. Only four days after classes started, the building was destroyed by fire under suspicion of arson. Classes continued in a nearby home. A less grand, but serviceable building was rebuilt by November of 1857. By then, the student body had grown to 150 students. On February 26, 1858, a second fire consumed the college again. Attempts were made to rebuild for a third time, but the Cumberland Presbyterian Church withdrew all financial support from the project. This being the eve of the Civil War, the church leadership was itself keenly divided by the issue of slavery, and Columbia College was yet another casualty of that acrimony. The school closed for good in 1860. The last remnants were torn down by 1867, with some of the old sandstone building blocks being used to build a store on Willamette Street (Eugene recycled even back then). Few present day reminders of Columbia College exist. The surrounding neighborhood is called College Hill, and there is a city-placed monument at 19th and Olive. The plaque reads: "Site of Columbia College 1856-1860". Carved into the stone base are the words "COLUMBIA COLLEGE FIRST SCHOOL OF HIGHER EDUCATION IN LANE COUNTY BUILT IN 1854". Only in operation for four years (not counting time closed for fires and rebuilding) it is not clear if any degrees were ever granted from Columbia College. However, several notable people did attend classes.

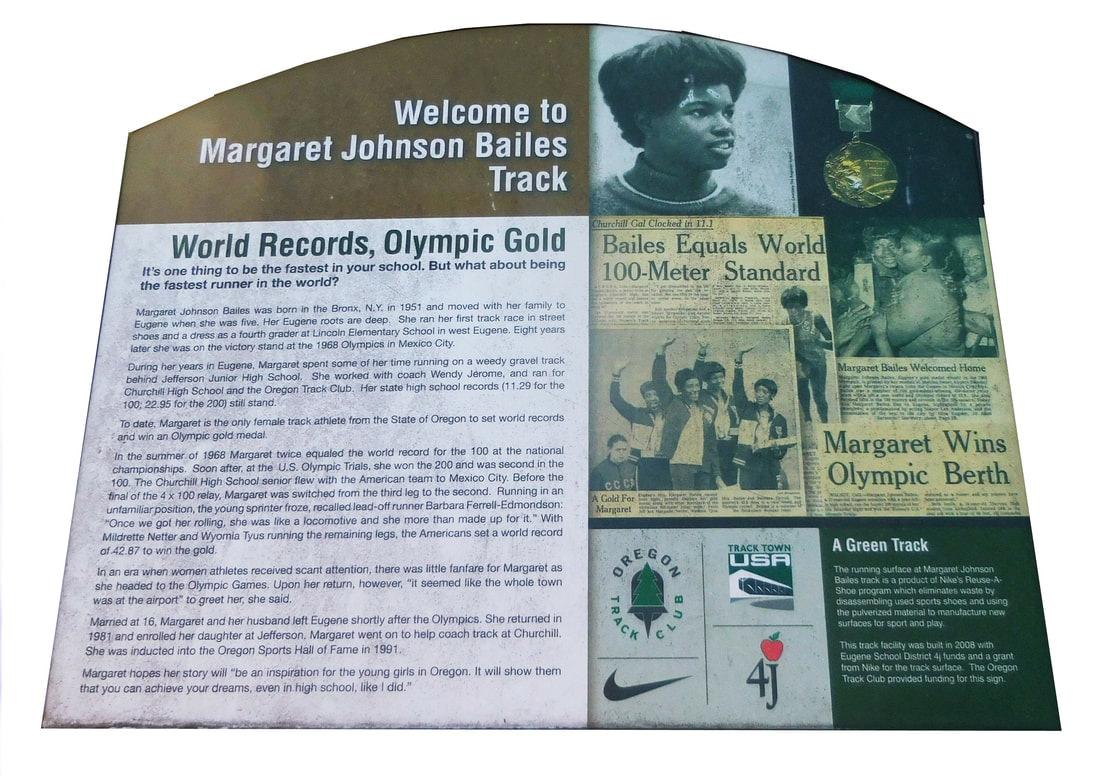

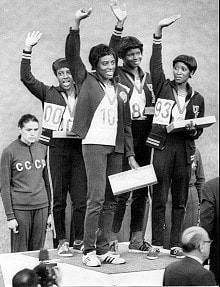

Harrison Rittenhouse Kincaid (January 3, 1836 – October 2, 1920) was an American printer, journalist, Republican politician, and university regent who served as Oregon Secretary of State between 1895 and 1899. In Eugene, Kincaid Street is named after him. Cincinnatus Heine Miller (September 8, 1837 – February 17, 1913), better known by his pen name Joaquin Miller, was an American poet and frontiersman. He is nicknamed the "Poet of the Sierras" after the Sierra Nevada, about which he wrote in his Songs of the Sierras (1871). Col. William Thompson (1846–1934) was an American-Indian fighter and journalist, the editor of multiple newspapers in Oregon and California. James Finley Watson (March 15, 1840 – June 12, 1897) was the 25th Associate Justice of the Oregon Supreme Court, serving from 1876 until 1878. Previously he served in the state legislature and later served as United States Attorney for the District of Oregon. By Gary Arnold If you have ever walked by the track in Westmoreland Park, you may have noticed the plaque. Great athletes deserve recognition, but after all, this is Eugene. Even Olympic level athletes aren't that uncommon. Is there anything to this story that deserves a second glance? Read on, and decide for yourself. Margaret Johnson was born in New York City, in the Bronx. Her father, Duke Johnson, moved the family out to Eugene when she was five years old because he decided Eugene would be a good place to raise his children. A pretty normal kid, she had no particular interest in sports. Just by happenstance, she was passing South Eugene High during an all-comers track meet. On a lark, she entered several events and did pretty well (even though she ran the events in dress shoes). Wendy Jerome was at the meet (wife of world class UO athlete Harry Jerome) and instantly realized that she was watching someone with exceptional talent. Wendy became Margaret's coach and soon ran into a problem. There were no other girls in Eugene that gave her any competition. So she started running against boys—same problem. She eventually was able to find a challenge by giving all her opponents head starts. As she grew older, she started training with some of the sprinters from the UO, and as a high schooler, she usually beat them in practice. At Churchill High School as a junior, Margaret won the 100- and 200-meter races in the state championship meet, and was part of the winning 4 x 100 relay team. That same year she set an American record in the 200 (22.95 seconds) and tied the world record in the 100 (11.1 seconds). As a senior, at the ripe old age of 17, Margaret ran a time of 11.30 seconds for the 100 meters and 22.95 seconds in the 200 meters. Those times were both good enough to win the state championship, in fact, they were both Oregon high school state records. Consider this: 50 years later, these marks still stand as Oregon high school state records. No one sets a track and field record that stands for 50 years. Her times were good enough to qualify her for the 1968 Olympic trials. At the trials she won the 100 and took a second in the 200. While staying in the Mexico City Olympic Village, she contracted pneumonia. She was unable to train for almost a week. Nowhere near full strength, she was able to place fifth in the 100-meter Olympic final (time of 11.3) and seventh in the 200-meter Olympic final (time of 23.1). Margaret had one more Olympic event left, the 4 x 100 relay. Barbara Ferrell would run the first leg, Margaret would run the second leg, Mildrette Netter ran the third, and Wyomia Tyus ran the anchor leg. Wyomia Tyus was the veteran of the group having won two gold medals in the 100 meters and the 4 x 100 relay four years earlier in the Tokyo Olympics. She had just won another gold medal in the Mexico City 100 meters, setting a new world record. Barbara Ferrell, in that same race, had taken the silver medal. The US fielded a strong team, but there were plenty of good sprinters competing. And several of the national teams had a lot more experience working together as relay teams. Poland was one of the favorites coming into the event, but they had dropped the baton in the qualifying heat and were out. You can watch the entire race. This is a classic sports film, and well worth watching, but the womens 4 x 100 begins at time 1:28:00 and runs through about 1:30:00. The US team did win in a time of 42.88, setting a new world record. But consider this: the first seven teams across the finish line also broke the previous world record. Imagine running a race where you run faster than anyone else ever has, and coming in seventh! The US team didn't break the record, they smashed it. The world record would stand until the Munich Olympics, four years later. And then came what is perhaps the most amazing part of the story. In today's world of woman's Title 9 access to sports scholarships, the pro track circuit and corporate shoe endorsements, it is difficult to remember a time when opportunities in sports were limited, especially to women and especially to women of color. After the Olympics, Margaret walked away from the world of sports and never competed again. By the time she was 17, she had married, had a daughter, and had moved to California. Years went by, and only family and Margaret's closest friends even knew of her accomplishments. But the record books had not forgotten her, and eventually a new generation of track fans began to discover the story.

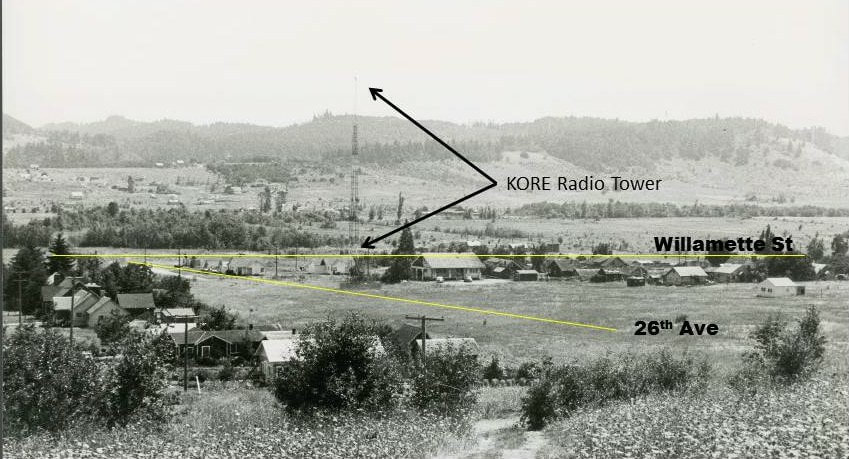

Margaret was inducted into the Oregon Sports Hall of Fame and the High School Track and Field Hall of Fame. She was invited to attend the 2008 Olympic Trials in Eugene as an honored guest. And the next year, the old Jefferson Middle School cinder track where Margaret used to train was re-built into a modern all-weather facility and dedicated as the Margaret Johnson Bailes Memorial Track. More Information The KORE radio station and transmission tower once stood along Willamette Street between 26th and 27th Avenues. The image (GN1330) above is courtesy of the Lane County History Museum and shows the South Willamette area circa 1942 as seen from approximately 25th and Olive (on the eastern flanks of College Hill) looking to the southeast. The street to the lower left is Summit (now called 25th). The KORE radio transmission tower is in the center of the image. The channel of the Amazon Creek is indicated by the dark patches of trees and shrubs in the distance.

KORE began broadcasting in 1927 in Portland. It soon moved to Springfield and then to Eugene. It is Eugene's oldest radio station. The current broadcasting tower is located on the banks of the Delta Ponds, just off Goodpasture Island Road. Originally built in 1945 as Brumwell's Friendly Service, the Friendly Street Garage was torn down in 2004. It was located near the corner of 27th Avenue and Friendly Street. It also served as a Shell gas station. The location has since been redeveloped and currently hosts residential units.

Originally, the Eugene Country Club (ECC) was located on College Hill. The 9-hole course ran between 24th and 28th Avenues and Willamette and Lawrence Streets. The club was founded in 1899. It is the second-oldest country club in the state. ECC filed articles of incorporation in February of 1913. It remained on College Hill into the mid 1920's when a new 18-hole course was opened at the current location on Country Club Road. The original course was not the verdant and manicured oasis we think of today. In reality, it was little more than a dusty pitch-and-putt without any kind of modern irrigation. The "greens" were made of sand (see picture below). It must have been a challenging course—the College Hill topography coupled with putts like this. The area of College Hill between Lincoln and Lawrence and 23rd and 25th is the repository for drinking water for the City of Eugene. When we turn on the kitchen tap, water the lawn, or wash the car, chances are the water we are using comes from one of three reservoirs located on College Hill. The reservoirs and green water tower are owned and operated by the Eugene Water and Electric Board (EWEB).

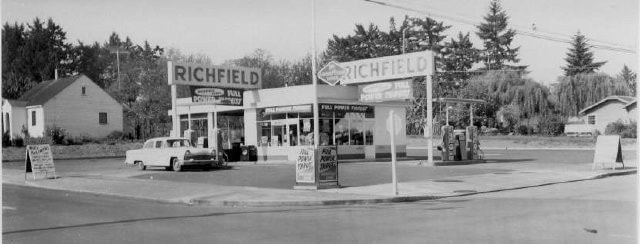

The oldest of these reservoirs is close to 23rd and Lawrence. This one is known as the 603 reservoir, which is the number of feet above sea level to the overflow pipe at the top of the reservoir. This large concrete tank began life about 1915. In the beginning it had an open top and was surrounded by a wrought iron rail. About 19 years later it was covered with the present concrete lid. This concrete tank holds about two and one-half million gallons of water when filled. Adjacent to this reservoir is the 607 reservoir, the large concrete structure with the pipe railing around the perimeter. The 607 reservoir was a product of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Public Works Administration and constructed in 1939. This reservoir is divided into two sections, north and south, which when combined hold some fifteen million gallons of water. This facility is teamed with a larger reservoir near 25th and Hawkins, and other facilities store a supply of drinking water for the City of Eugene. At the very top of the Friendly Area Neighborhood is the 703 reservoir, also completed in 1939. This steel tank is about thirty feet in diameter and twenty feet tall. Its six legs raise it some seven hundred feet above sea level where its red blinking light can be seen from most of downtown. This reservoir holds about one hundred thousand gallons and serves the homes in the immediate area which would have insufficient water pressure if gravity fed from the adjacent in-ground storage. By Greg Giesy, Friendly Area Neighbors former Board member and longtime Friendly resident. Originally printed in the Summer 2011 edition of the Friendly Area Neighborhood Newsletter. Several neighborhood people were asked by Andrew, our newsletter editor, to write an article about Willamette Street both looking at the past and hopes for the future. Because I am a long-time resident and grew up in the Friendly neighborhood, he asked me in particular to talk on the past of Willamette Street. My earliest memory of anything on Willamette Street was at about four years old going to the grocery store that is now Capella with my father (Willamette Street between 24th and 25th Avenues). He soon switched to the Big Y Market on 6th Avenue and then to the Little Y on 19th and Jefferson, which was a full service grocery store in those days, with even a butcher. There was a gasoline service station across the street from the Little Y so I didn’t see Willamette again until grade school. I attended Francis Willard Grade School, and occasionally after school I was allowed to go to a friend's house on Pearl south of 29th. We would walk by the Eugene Drive-In Theater's sheet metal walls and past the drive-in's screen to a grocery store on the northwest corner of 29th and Willamette. The store had packages of flat gum with three baseball or football cards for two or three cents. The gum as I recall was terrible but we were after the trading cards.

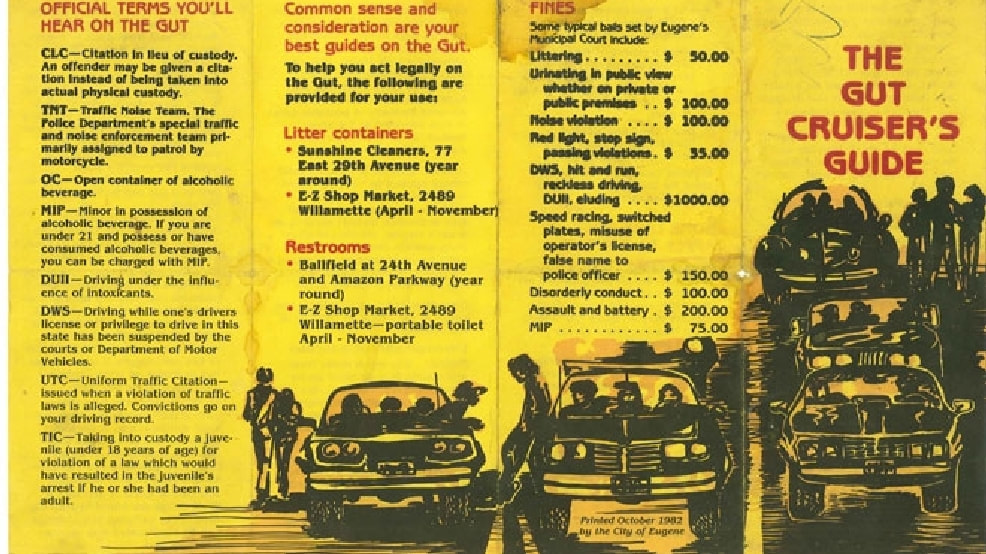

The drive-in theater took up most of what is Woodfield Station today. The screen faced into the hillside, and home owners above could pay the drive-in a monthly fee to have a speaker (that you normally hooked to your car window) wired in their living rooms, so they could watch the movies with sound out their picture window. Summers were partly taken up with swimming lessons at Amazon Pool. Willamette was the biggest street I needed to cross on my way to the pool because there was no Amazon Parkway at the time.  By Greg Giesy, Friendly Area Neighbors former Board member and longtime Friendly resident. Originally printed in the Summer 2011 edition of the Friendly Area Neighborhood Newsletter Willamette up to my teenage years was mostly vague memories but the lure of the automobile, girls, and "The Gut" was to become some of my fondest memories. For those of you that don't know, Willamette Street was called "The Gut". And "The Gut" held the imagination of Lane County teenagers with cars from the 1950's into the 1980's, and I was there for its heyday in the 1960's and saw the start of its slow death in the beginning of the 1970's. The original Gut started in downtown Eugene at 6th & Willamette and went to the A&W Root Beer Drive-in Restaurant on the southeast corner of 29th & Willamette, then back down Willamette to 20th, with the turn over to Oak, and on down to 6th to start the track again back up Willamette. Why? The car was freedom, fun, and adventure. You could escape your problems, worries, and especially your parents with your friends, and luckily gas was cheap. The Gut was originally broken up in sections, with the important ones being downtown, because there was a traffic light at each block so you could talk to the car next to you on a one-way street at each light, 13th to 18th for a not-so-serious drag race, 24th to 29th to yell at people going by, and driving through the parking lot at A&W to see who was there. The Eugene Downtown Mall closing Willamette from 6th to 11th was to make "The Gut" smaller and more problematic as it eventually became just 24th to 29th with more teenagers in cars coming from Pleasant Hill, Creswell, and Cottage Grove. Friday and Saturday was even more crowded than the other days of the week, with bumper-to-bumper traffic from late afternoon into the early morning. Kids tried to park with the cramped conditions and higher gas prices, while merchants got tired of the nonsense with no trespassing signs and the police.

"The Gut" faded away by the 1990's to the relief of merchants, the police, and the City in general. Kids found other things to do with their time, and some of us went on with our lives, having memories of a different time without expensive gas, concerns of pollution, and global warming. Willamette Street hasn't changed much from the 1960's, with destination merchants still relying on the car to bring most if not all of their business. My hope for the future is that we house enough people around the south Willamette area with denser housing and change the road to three car lanes and bike lanes so that more people will use Willamette as a place to enjoy in a different way without the car that has been so important to Willamette Street's history. |

AuthorFriendly Area Neighbors Archives

June 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed