|

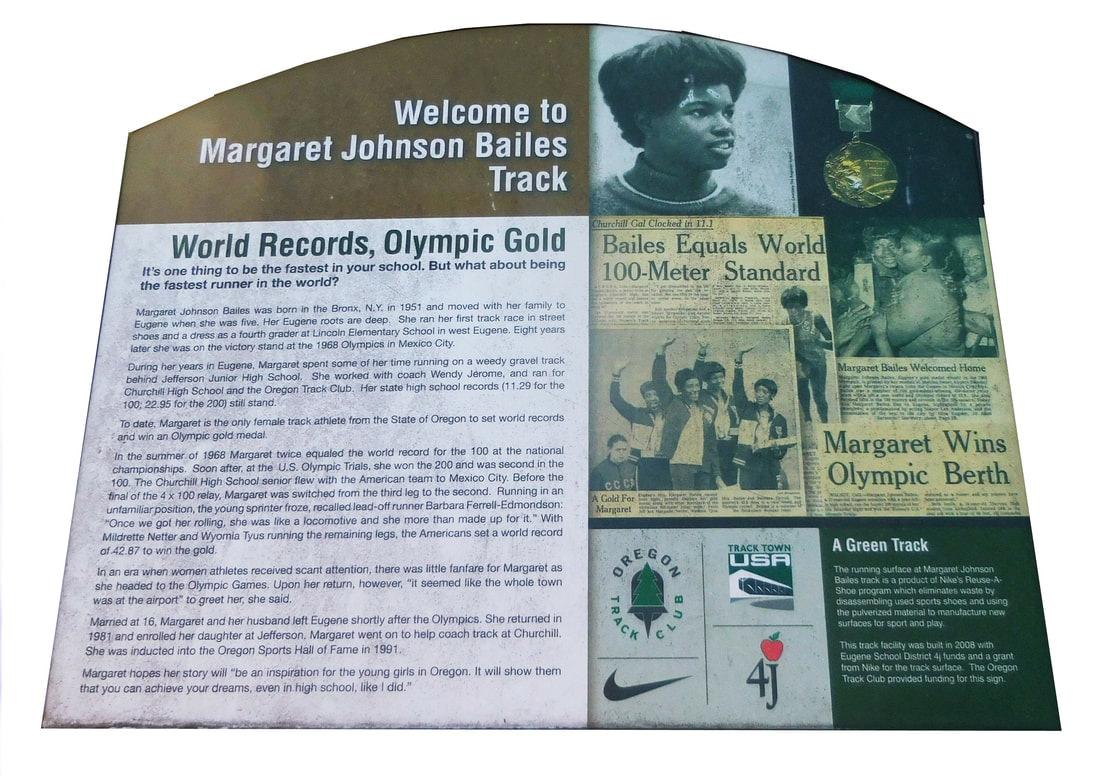

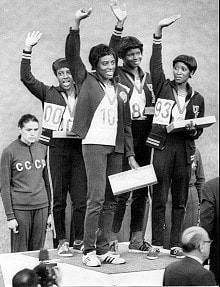

By Gary Arnold If you have ever walked by the track in Westmoreland Park, you may have noticed the plaque. Great athletes deserve recognition, but after all, this is Eugene. Even Olympic level athletes aren't that uncommon. Is there anything to this story that deserves a second glance? Read on, and decide for yourself. Margaret Johnson was born in New York City, in the Bronx. Her father, Duke Johnson, moved the family out to Eugene when she was five years old because he decided Eugene would be a good place to raise his children. A pretty normal kid, she had no particular interest in sports. Just by happenstance, she was passing South Eugene High during an all-comers track meet. On a lark, she entered several events and did pretty well (even though she ran the events in dress shoes). Wendy Jerome was at the meet (wife of world class UO athlete Harry Jerome) and instantly realized that she was watching someone with exceptional talent. Wendy became Margaret's coach and soon ran into a problem. There were no other girls in Eugene that gave her any competition. So she started running against boys—same problem. She eventually was able to find a challenge by giving all her opponents head starts. As she grew older, she started training with some of the sprinters from the UO, and as a high schooler, she usually beat them in practice. At Churchill High School as a junior, Margaret won the 100- and 200-meter races in the state championship meet, and was part of the winning 4 x 100 relay team. That same year she set an American record in the 200 (22.95 seconds) and tied the world record in the 100 (11.1 seconds). As a senior, at the ripe old age of 17, Margaret ran a time of 11.30 seconds for the 100 meters and 22.95 seconds in the 200 meters. Those times were both good enough to win the state championship, in fact, they were both Oregon high school state records. Consider this: 50 years later, these marks still stand as Oregon high school state records. No one sets a track and field record that stands for 50 years. Her times were good enough to qualify her for the 1968 Olympic trials. At the trials she won the 100 and took a second in the 200. While staying in the Mexico City Olympic Village, she contracted pneumonia. She was unable to train for almost a week. Nowhere near full strength, she was able to place fifth in the 100-meter Olympic final (time of 11.3) and seventh in the 200-meter Olympic final (time of 23.1). Margaret had one more Olympic event left, the 4 x 100 relay. Barbara Ferrell would run the first leg, Margaret would run the second leg, Mildrette Netter ran the third, and Wyomia Tyus ran the anchor leg. Wyomia Tyus was the veteran of the group having won two gold medals in the 100 meters and the 4 x 100 relay four years earlier in the Tokyo Olympics. She had just won another gold medal in the Mexico City 100 meters, setting a new world record. Barbara Ferrell, in that same race, had taken the silver medal. The US fielded a strong team, but there were plenty of good sprinters competing. And several of the national teams had a lot more experience working together as relay teams. Poland was one of the favorites coming into the event, but they had dropped the baton in the qualifying heat and were out. You can watch the entire race. This is a classic sports film, and well worth watching, but the womens 4 x 100 begins at time 1:28:00 and runs through about 1:30:00. The US team did win in a time of 42.88, setting a new world record. But consider this: the first seven teams across the finish line also broke the previous world record. Imagine running a race where you run faster than anyone else ever has, and coming in seventh! The US team didn't break the record, they smashed it. The world record would stand until the Munich Olympics, four years later. And then came what is perhaps the most amazing part of the story. In today's world of woman's Title 9 access to sports scholarships, the pro track circuit and corporate shoe endorsements, it is difficult to remember a time when opportunities in sports were limited, especially to women and especially to women of color. After the Olympics, Margaret walked away from the world of sports and never competed again. By the time she was 17, she had married, had a daughter, and had moved to California. Years went by, and only family and Margaret's closest friends even knew of her accomplishments. But the record books had not forgotten her, and eventually a new generation of track fans began to discover the story.

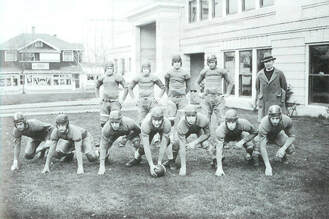

Margaret was inducted into the Oregon Sports Hall of Fame and the High School Track and Field Hall of Fame. She was invited to attend the 2008 Olympic Trials in Eugene as an honored guest. And the next year, the old Jefferson Middle School cinder track where Margaret used to train was re-built into a modern all-weather facility and dedicated as the Margaret Johnson Bailes Memorial Track. More Information Compiled by Natalie Perrin By 1937 in Eugene, Oregon, there was a growing need for an athletic field, both for the community and the schools. On December 3rd, 1937, the Eugene Register-Guard printed the first article referencing the "Big Amazon Park Project." By December 8th, 1937, a committee had been formed by the Eugene Chamber of Commerce and plans were being formulated for a new athletic field to be built through the cooperation of the Chamber Committee, the Eugene Public School Board, and the Eugene City Council. By December 24th, 1937, the WPA was reported to be interested in the development and building of the recreation center. On January 11, 1938, the Register-Guard presented the facts regarding the financial plans for the new athletic field. The city council was asked to turn over the land known as the Amazon tract, which was held for $6000 in back taxes. The school board was asked to contribute $6000, and the committee guaranteed to raise another $6000 so the first year work could be completed. The WPA was set to contribute the labor. The $12,000 contributed by the school board and the committee would be enough to grade the field and build the covered grandstand, which would seat 4,000 people. On January 26, 1938, the Register-Guard reported that the "Park Project is Threatened by Deadlock." The concern of who would pay the $6000 in back tax assessments, the city or the school board, seemed to spell the end of the project. Without the deed from the city, the school board was concerned that they would not be able to secure the WPA for the project. The controversy lasted months, until it was decided to put the vote to the community at large. On Friday, May 20th, 1938, Eugene citizens went to the polls to vote on the issue to levy a one-half mill tax ($0.50 per $1000 of assessed property value) to repay the debt of $6000 in outstanding liens to the property. Voters approved the project by an almost 2-1 margin, enabling the proposed athletic field to move forward. The title to the Amazon tract was deeded over to Eugene Public School District 4J on June 13th, 1938 to "be used as a recreation area for the School District and for the municipality." Eugene Civic Stadium would never have been constructed without the display of outstanding public support it received and the cooperation of the numerous civic agencies involved. This unique cohesion of community development and city planning illustrates the camaraderie apparent in WPA projects built throughout the country during the Depression-era. The stadium meets Criterion A for its distinctive characteristics of community planning and development, which brought the government and community together during these difficult times. On May 15, 1938, just prior to the special election, the Eugene Register-Guard presented a plan to the public for the proposed development of the Amazon tract area. The proposed site would include a football and baseball field and grandstand, track field, swimming pool, tennis courts, shuffle board and Ping-Pong courts. The plan was to begin on the football and baseball field first, with the other areas being developed later. Work began on June 21, 1938, with Jay F. Oldham contracted for the grading of the land. Graham Smith, a local of Eugene, was named architect for the grandstand, the plans of which were approved in July. Smith, along with the manpower of the WPA, utilized local old growth Douglas fir exclusively in the construction of the grandstand. The work was completed in mid-September, and a dedication ceremony featuring the Eugene High School marching band was held on October 22, 1938.  Eugene High School Football Team, circa 1930. Current site of the Cornucopia Restaurant (in background). Eugene High School Football Team, circa 1930. Current site of the Cornucopia Restaurant (in background).Photo Courtesy of the Lane County History Museum. The first event at Civic Stadium, the annual rivalry football match between Eugene High and Corvallis High, was held on October 28, 1938. The grandstand still did not have a roof, and both players and fans were rain-soaked by the end of the game. The match, played on the clay and sawdust field, ended in a 0-0 tie. By the 1939 football season, floodlights and the grandstand roof had been erected at Civic Stadium. The roof was designed by the West Coast Lumberman's Association of Seattle, Washington, and utilizes the same local, old growth Douglas fir that can be found in the grandstand construction. Plans for the other parts of the athletic complex never materialized and the land was developed into South Eugene High School.  Eugene High School Football Game, November 11, 1953 Eugene High School Football Game, November 11, 1953 During the period of significance (1938 - 1955), Eugene Civic Stadium was primarily home to high school football, baseball, and soccer games. The stadium was designed as a multi-use facility, and converted easily for various types of sporting events. Eugene Civic Stadium has been home to numerous high school ball games, graduations, 4th of July celebrations and even rodeos throughout the years. In 1941 the School District added the Heating Plant, a small ancillary building with an 880 gallon water tank, to the site. The Heating Plant initially acted as the sole source for hot water at the stadium, and serviced the locker and bath rooms by utilizing sawdust to run the boiler. The building, through structurally unaltered, has not served its initial function since the water tank was removed, and today is utilized as a storage facility for the site. In 1946 the School District added the Garage and Living Quarters, which functioned on the ground level as a repair garage for the Bus Depot that, at that time, was located in what is now the parking area. With the stadium operating both Saturday night and Sunday afternoon for hardball games and at least twice a week for softball, the groundskeeper was on duty 24 hours per day. Recognizing that this was a full time job, the School District of the time built two apartments above the garage for the Groundskeeper and his family. The initial groundskeeper was William "Grady" Lewis, who was a WPA foreman for the Eugene Civic Stadium project. When the stadium was completed he was asked to stay on and run the facility. Mr. Lewis' son, Graydon Lewis, who is still living in Eugene, remembers life as a boy at Civic. Living in a nearby house prior to the construction of the Garage and Living Quarters, Mr. Lewis assisted his mother and father by helping to clean the stadium on Sunday mornings while his father drug and marked the sand field. Mr. Lewis remembers the stadium as a playground for himself and his friends, and knew everything under the grandstand including places to find change dropped during the games. Though Mr. Lewis, the younger, never lived in the Garage and Living Quarters (he joined the Navy at this time), he remembers it as "a fine apartment" for his family. Sometime in 1950 - 55, the Maintenance Office was constructed. This building acted as a storage facility for equipment needed to grade and paint the field. The building served as an office and maintenance building for the groundskeeper, as well as the player's lounge.  In 1969, Civic Stadium became home to Eugene's own minor league baseball team, the Emeralds. Upgraded to the Class AAA Pacific Coast League, the Eugene Emeralds required a larger facility than they currently had, and sought the assistance of the Eugene School District when plans to build a new stadium were unsuccessful. Baseball had not been played at Civic Stadium in over twenty years, but the team was granted a three-year lease to use and improve the stadium. It was in 1969 that the stadium was updated, converting it from its almost full-time status as a football stadium into a baseball facility. Two large light standards and 800 wooden, theatre-style box seats were purchased from the soon to be demolished River Island Stadium, which had been home to the San Diego Padres minor league team since 1936. The light standards were added to the roof of the Grandstand, and the box seats were placed on risers in front of the original stands to allow for additional seating.  The press box was relocated at this time as well, having originally been located on the Grandstand roof. A new press box was built into the seating, in the curve of the L-shaped Grandstand, and is clad in vertical wooden board-and-batten siding. The field was updated and the concession area paved. Other improvements ranged from new paint to new fencing. A metal, hand-turned score board was installed, which added to the character of the park. The wooden risers were replaced in 1986 by the current blue plastic risers, due to the accelerated rot and deterioration that had occurred in their exposed, uncovered placement. Additional improvements have been made over the years including adding sprinklers and bringing the site up to the standards of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). However, in spite of continued improvements, Eugene Civic Stadium retained integrity of location, setting, materials, design, workmanship, feeling and association. The Eugene Emeralds are ranked as one of the most popular teams of the Northwest League, having drawn no less than 100,000 fans per year since 1985. As of opening day 2008, Eugene Civic Stadium was the 9th Oldest Minor League Ballpark in the United States. It was the third oldest minor league stadium in use west of the Rocky Mountains. Civic Stadium was a place where the community enjoyed America's favorite pastime every summer, and is a part of Eugene's history. Continuously used as a municipal athletic facility since its inception, Eugene Civic Stadium met National Register Criterion A for its initial and continued contribution to the entertainment and recreational needs of Eugene and the surrounding communities in the Pacific Northwest. Civic Stadium Timeline:

Civic Stadium was built in 1938 as a partnership of city government, the business community, Eugene citizens and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). What they built was a Douglas fir masterpiece that became a magnet for area youngsters and their families. Summer evenings at Civic watching a ballgame, a moonrise and with new friends sitting beside you are a fond memory of those who grew up in Eugene from the 70's to 2009.

The raging summer fire that consumed Civic in 2015 seemed to crush the dreams of those who had fought to restore the grandstand for continued use by the community but Eugene Civic Alliance has persisted with a plan to create a new home for Kidsports and a venue worthy of the name Civic. Civic Park is now under construction and is scheduled to open in 2020. (Photos courtesy of "Eugene's Civic Stadium" by Joe Blakely (roofless stands) Greg Giesy (fire) and Marv VanWyck (post fire)). |

AuthorFriendly Area Neighbors Archives

June 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed