|

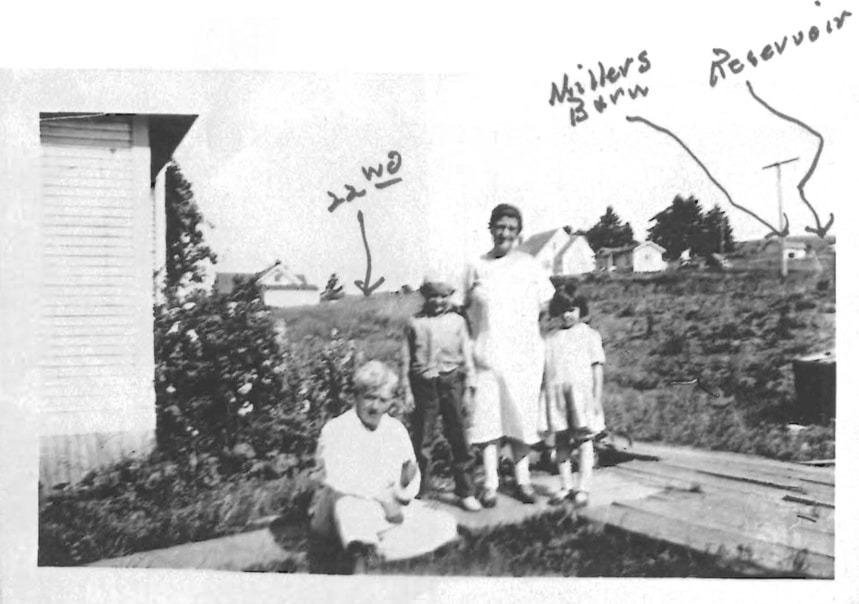

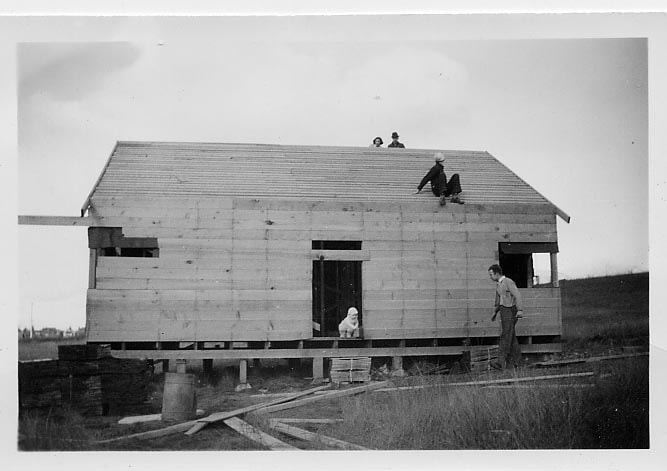

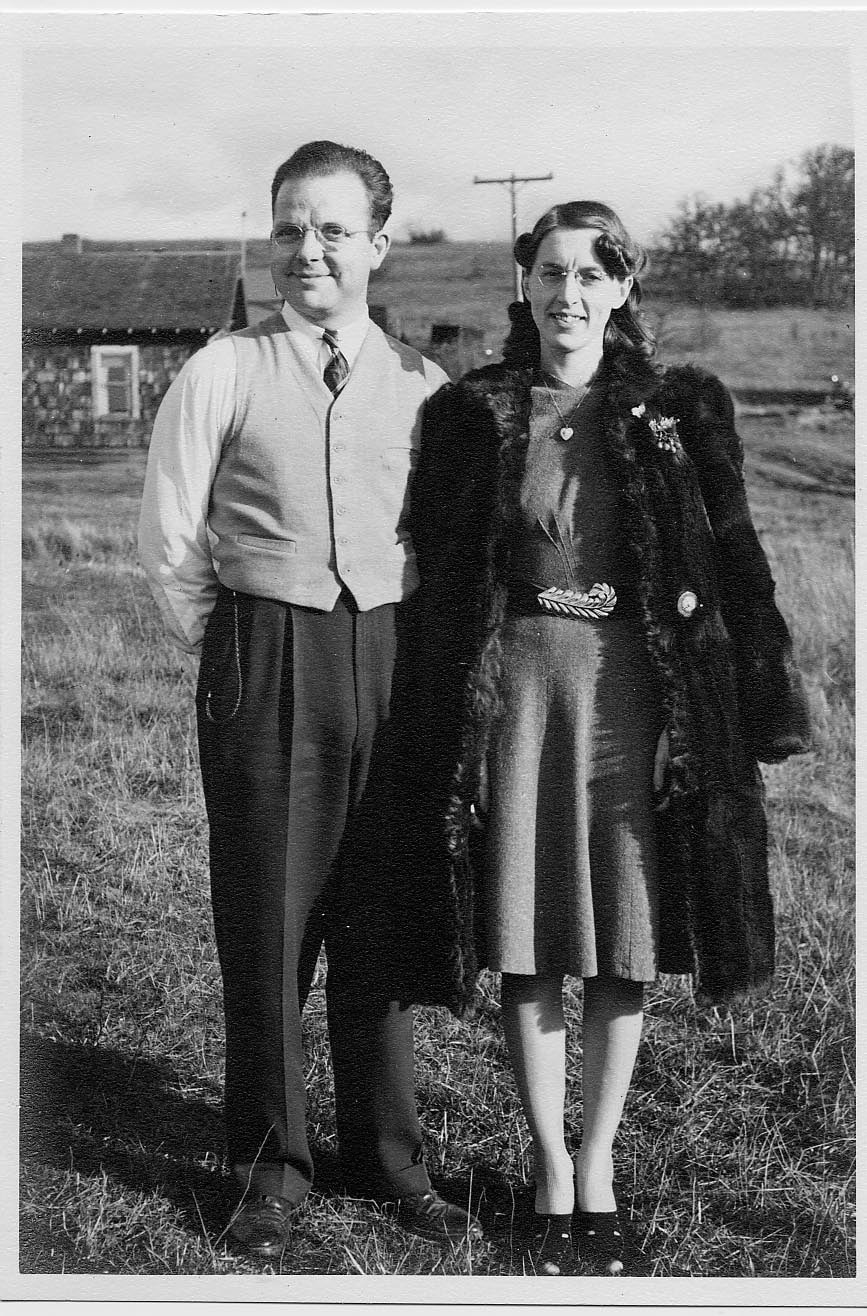

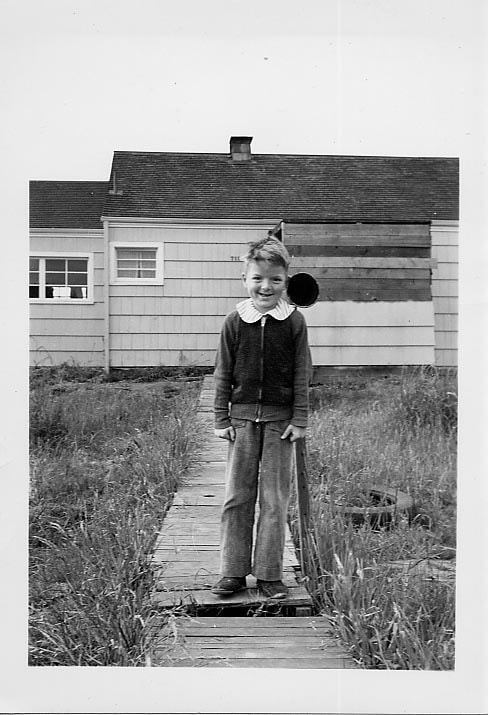

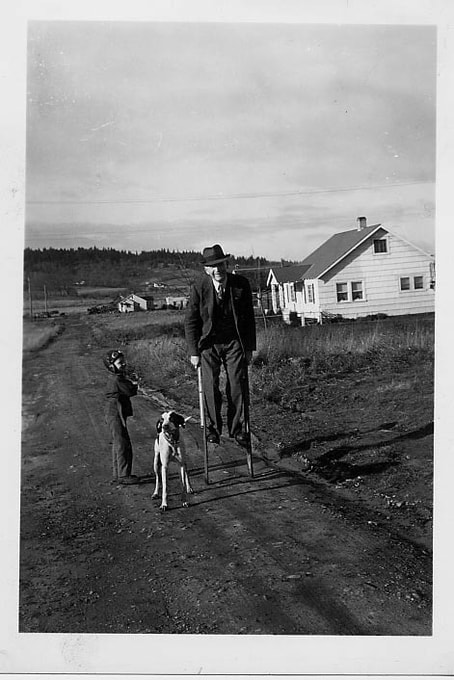

Photos courtesy of Ed Barthelemy  Barthelemy Family at the southwestcorner of their home. The exact date is unknown. Possibly the late 1920's. We are looking to the east, with College Hill rising off the right side of the image. Although obscured by the grassy slope in this image, Washington Street lies behind the people in the photograph but before the homes in the background. Photos and descriptions courtesy of Wes Nelson by Ed Barthelemy Our home at 2162 Washington Street was the last house on the west side of the street, and there was only one on the east side between 19th and 22nd directly across the street from us. As I recall we paid $2,000 for the house in 1923. I was 4 years old. The street itself was never paved from 19th south, until after I left home in 1940. It ended at 22nd with a pair of ruts continuing on to the only house above 22nd on the east. From there south, from Jefferson to Lawrence, was vacant to 29th. Though at that time it wasn't called 29th; it was the Lorane Highway. The folks that graded 22nd Avenue at Lawrence Street apparently used the same transit at Washington. It was paved to the east side of Washington with a three-foot bank running north and south, leaving one lane on the north side of 22nd from which to turn right onto Washington. 22nd did not continue on to Jefferson and was absolutely impassible in the Winter. A very substantial ditch ran down the east side from 22nd to 19th. With no storm drains it was quite a waterway in a heavy rain. At all other times it presented a real driving hazard, summer or winter. Once in, there was no getting out on your own. While I suppose there were towing companies, I don't ever remember seeing one. You simply called a friend, and he hooked on and snaked you out. A couple of things that Washington Street meant to me were really not limited to that street. The first was the Newman Fish Truck, operated by the original Mr. Newman. It was a black Model-T, rigged up with what today would be called a canopy and a hanging scale. He would drop the tailgate and slice off whatever you wanted. It sounds pretty grim, but he had the fish on ice, which he shared with us little kids. I don't really know why he came only on Friday, but I suspect he had a list of good Catholics. The other was a traveling grocery store, that came—I don't remember the frequency—probably a couple times a week. It looked somewhat like an old school bus, but no windows. It was all shelves inside. I'm not sure, but I think it had solid rubber tires too. I vaguely remember him pulling up in front of the house (he always honked) and throwing one of us a block of wood to put behind the rear wheel to keep it from rolling backwards. As little kids we used to watch for him and see who got to put the block of wood he carried under the back wheel. I guess it was heavy, that just putting it in gear wouldn't hold. I guess we never wondered about the brake or the hazard involved in accomplishing that manly task. I don't know how it worked, but he had a small freezer that held a few quarts or probably pints of ice cream. But most important of all, he introduced us to frozen Milky Way bars. I even remember him inferring that they would keep us cool. Or maybe that was our own conclusion. Naturally, things were a little more expensive, but the convenience was hard to beat. It had an extremely limited selection of canned and packaged food, but it was convenient. As I think more about it, it was probably the forerunner of the 7/11. We got a sidewalk somewhere in that period around 1930, but it ended at the south side of our lot and did not run across 21st or 20th. The latter wasn't too bad, but 21st fell victim to the demon transit that was used on 22nd. With a little hand digging and laying of some planks, it was passable, though hazardous when wet. The closest bus was at 19th and Washington and ran east. Seldom used though, because it cost 5¢. 22nd Avenue When I was a kid growing up at 2162 Washington Street here in Eugene, that number (22nd) had a meaning far more meaningful than a number. Actually 22nd meant the street, which at that time ran from Washington to Willamette—no further in either east or west, unless you want to be really technical and include the block from Jefferson to Madison. That wasn't really much more than a long driveway to a house on the corner of Madison and what you could call 22nd, although there were no houses on that stretch of 22nd. It wasn't even graveled. I have no clear recollection of 22nd before it was paved, and even that mostly involved the three blocks east from Washington. In other words up to Charnelton, not because we were restricted to that area, but rather it was because so much of our free time was spent "above 22nd". Charnelton ended at 24th and dropped off into a ravine. As hard as it is for some folks to believe, it was the city dump, but that's another story. [Editor's note: That is very near where the city drinking water reservoir is today.] The intersection of 22nd and Washington, as I look back on it, was something to behold. Washington for all intents as a street ended there. A one-lane gravel driveway ran about a half-block to the lone house on the east side. To the west towards Jefferson street, there was absolutely nothing to indicate vehicular passage. Washington was blacktopped, but not the way it is done today: no curbs or gutters, and just a center stripe. Actually it was probably just oiled, with a rather deep ditch on the east side. This brings us back to 22nd. It would be interesting to study the engineering that went into the paving, not so much the pouring as the grading. The problem started at Charnelton, and the cut was so deep that it left high banks—probably ten feet—on the uphill (south) side, most noticeably between Lawrence and Washington. I'll get back to that Lawrence Street bank. At Washington the pavement ended at the original street right-of-way, which is normal, but the problem was that the grade was about five feet below the street. In other words as one would come down (westward) on 22nd, he encountered a dirt bank. As a solution the north half of 22nd was opened up by lowering the bank so one could get onto Washington. The other half remained blocked for a number of years, as I recall, probably until Washington was paved. As I mentioned above, the cut prior to paving seemed quite excessive and unnecessarily deep. Bear in mind that this was done in the Depression years, so anything that would create work was acceptable. The actual digging was done mostly with what was called a Fresno[1]. There may have been minor variations of this device, which had other names, but basically it was a horse drawn scoop operated by a man guiding direction and depth by means of two handles. It was something like a plow, but with a scoop. This was then loaded into horse-drawn wagons that opened on the bottom, like the bomb-bay doors on a bomber. If this sounds slow, it was, and while manpower was the least of the problems, getting rid of all that dirt took some head scratching. Now bear in mind that 2162 Washington (our house) was the last house on the west side. I mentioned the one house above 22nd on the east side in an earlier paragraph. There was much vacant property between us and the Lorane Highway, but for some reason, probably because it was city-owned, they decided to dump all that dirt on the lot adjoining our property on the south (between us and 22nd). It was piled up six or eight feet. There was no attempt made to flatten it either. It was all long humps just as dumped from the "bomb-bay doors", and so it remained all through my childhood. I have no recollection whatever of seeing any machinery such as a bulldozer that might have been used for grading. WPA [Editor's Note: Work Project Administration-A depression era program that aimed to put the unemployed back to work] were very common and that might possibly have been one. Otherwise it was Fresnos, horses and wagons, and men and shovels. Let's go back to Lawrence street. It ended at 22nd and while it probably deserves separate acknowledgment, I must expound on a couple of characteristics that reflected on 22nd. From 22nd to 24th was a dirt road that ran up along the west side of the reservoir without a hint of gravel. In the winter one could drive down, but not up. The reservoir also deserves a separate recognition, but for now visualize it as an open concrete box with a spiked fence around it. When constructed the excavation dirt was dropped off and more or less aligned with Lawrence. Needless to say love and feminine challenges demanded risking prized possession by driving off this cliff. I must add that access to the plateau was gained by one of three upward ramps on the east side, which got progressively steep from the southernmost to the north. All of these activities presented no problem until 22nd was put in leaving the high bank referred to earlier. More than one brave, inebriated, or femininely challenged lothario plummeted off the cliff, down Lawrence, and probably with brakes mashed to the floor found himself (too late) staring at 22nd ten feet or so below. There was not a car built that could withstand the result. Although as I recall, the young bodies did. After a couple of these incidents, a fence was constructed, but it served as nothing more than a preliminary indication of what was to come. I think the bank was eventually bladed down to offer a more gradual descent to 22nd. Naturally, the obvious hazards had the risks compounded when accomplished at night. That particular street (22nd) held no significance until I reached high school. This was in the middle 1930's, when as designed by nature it became one criterion by which we judged cars. This takes us all the way over the hill to Willamette. We found that it took a really good car to go over the top in high gear. That sounds rather simple until one bears in mind that we had to turn the corner prior to starting the ascent. As best I recall, anything less than 35 miles per hour didn't cut it. Today it is relatively easy, but one must remember that the best of those cars had 85 horse power. Lawrence Street in retrospect had some interesting sociological ramifications, especially the part from 13th south. This was not a street which I as a kid would walk alone from school at 11th and Lincoln. I could name names, but prefer not to, of the tough kids that lived on that street all the way up to 20th. I'm sure some are still alive. Eugene High was at 17th and Lincoln. Their football field ran from 19th to 20th and Lawrence to Washington. At one time it had high board tight-spaced fence all around, presumably to keep out spies from University High or Springfield High. 20th did not run through from Lawrence (nor did 21st) but some optimistic contractor dug four or five holes on the south side of 20th, which were to be basements of homes, but remained for years as just water filled holes. The soil in that area is just about the best example of gray clay to be found in the valley. Naturally the best WPA wisdom running south from 20th was selected as a terracing project for what eventually became Washington Park (Lawrence to Washington). Now if I were to leave it at that, one would have visions of earth-movers, D-8s[2] and huge dump trucks, with much noise and smoke. But not so. Not a sound. Every bit of that work was done with hand shovels and wheelbarrows. And don't forget the sticky clay. Each shovel full had to be scraped off into the wheelbarrow. What today would have been done in an afternoon actually took months and at least part of it in the rainy season. Maybe longer. To close the Lawrence Street saga, loosely speaking it ran up along the west side of the reservoir. It was more like a trail until at about 24th, it dead-ended at the north boundary of the Eugene Country Club. Back to the tough kid on Lawrence. For some strange reason it was like an island. Lincoln, Charnelton, Olive, no problem. Ditto for Washington, which was a "newer" street and was about three notches up the social ladder from any of the others. This applied mainly to the strip from 19th north, all the way to at least 8th. Much nicer houses, many professional people. Jefferson Street slid back down the social ladder. I'm not sure why, though the street car (trolley) did run on Jefferson. I can't recall where it entered north of 19th, but it did run from there (19th) to about 24th or 25th, where it turned west down to Friendly, south to 29th, east to Willamette, north to town, and so on. Now picking a few random thoughts that may have some bearing on the earlier part of this epistle. The lone house above 22nd on the east side of Washington was originally owned and built by the Miller family. He had what might be loosely referred to as a dairy. I think he owned around five cows with a little barn or shed southwest of the house and up the hill. It was beyond my comprehension that 22nd would ever be paved from Washington to the west. Even in the Summer a car might break through the clay crust into the mud. We had a cow that we "staked out" in the "pasture" between 22nd all the way to 29th, and between Washington and Jefferson. The chain was about 50 feet long, and as a stake we seemed to always have a car axle which was driven into the ground. Our mailman was Mr. Taylor. He lived on the southwest corner of 20th and Washington, and he made ninety bucks a month. Hard to imagine how impressed we were. Of course you could buy a brand new Ford for about $450, but the only ones we knew who had a new car were related to the Buick dealer. 23rd and Lincoln brings back a couple of memories, neither of which strikes me as anything short of stupid. Manholes at least in that location had cement covers about 3 inches thick, around 30 inches in diameter, and mighty heavy, but not so heavy that a group of idiots couldn't get it out of its horizontal position and roll it down Lincoln. I'm sure that thing would have gone all the way to the Butte, but it veered left at 22nd, went in one side of a house and out the other, and for whatever reason didn't do a whole lot of damage. The other incident occurred while I was in high school. My closest friend was one of those referred to earlier whose dad owned a new car, a classy midnight blue '39 Buick[3] with fender mounts. We "parked" on Lincoln north of 23rd facing north with a view of the town. When we were finished doing whatever it was we were doing (not much) my friend released the brake and we proceeded down, picking up more speed than I like to think about. All was fine until we got to about 21st. At that point we collectively discovered that this vehicle had a steering wheel lock that had not been disengaged. It could have ended in a disaster had God not put an old Nash in our way. Now when they say built like a Buick, there can be no other reason for my present existence. Can't say as much for the Nash. His dad didn't even yell at him (my friend's dad). Earlier I referred to the County Club running south from about 24th. The clubhouse as near as I can picture it was about in back of (west) of Baskin Robbins which now fronts Willamette.

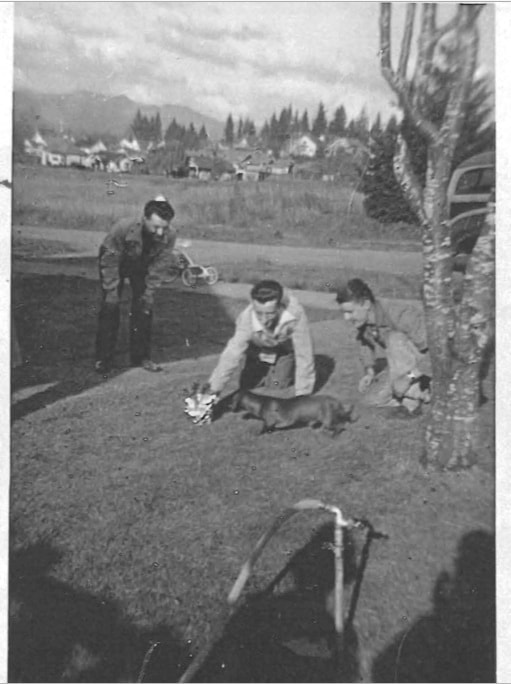

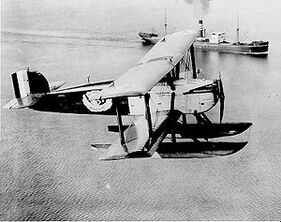

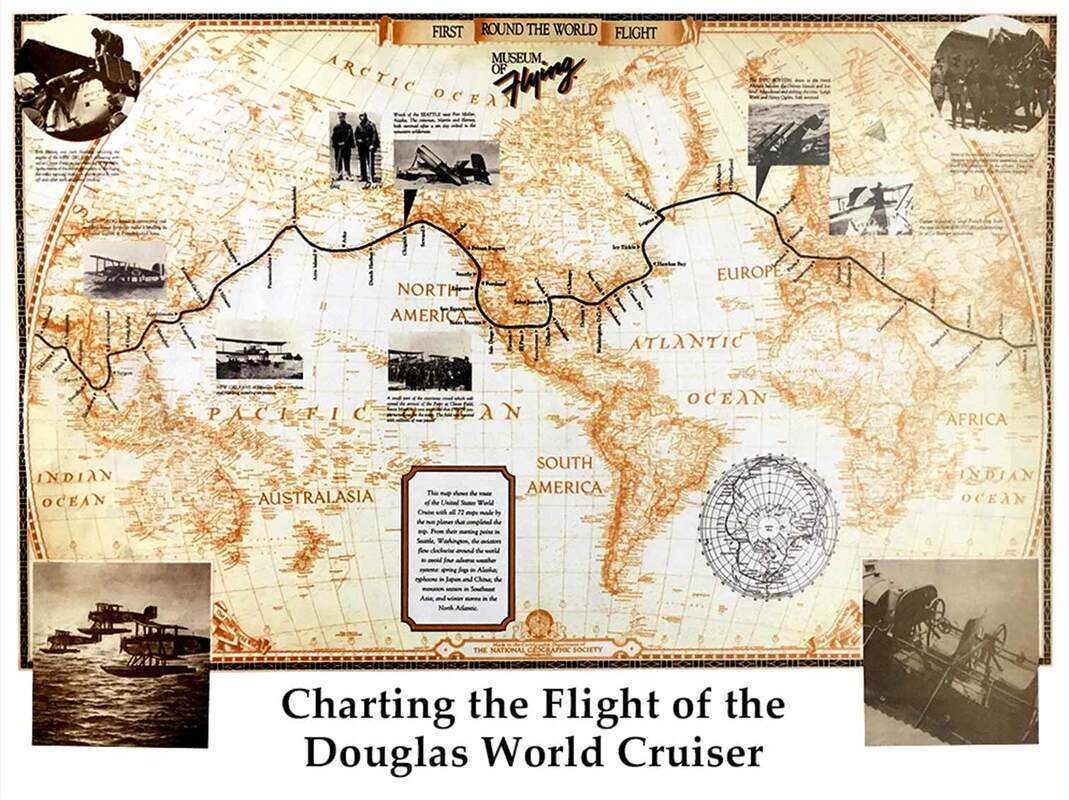

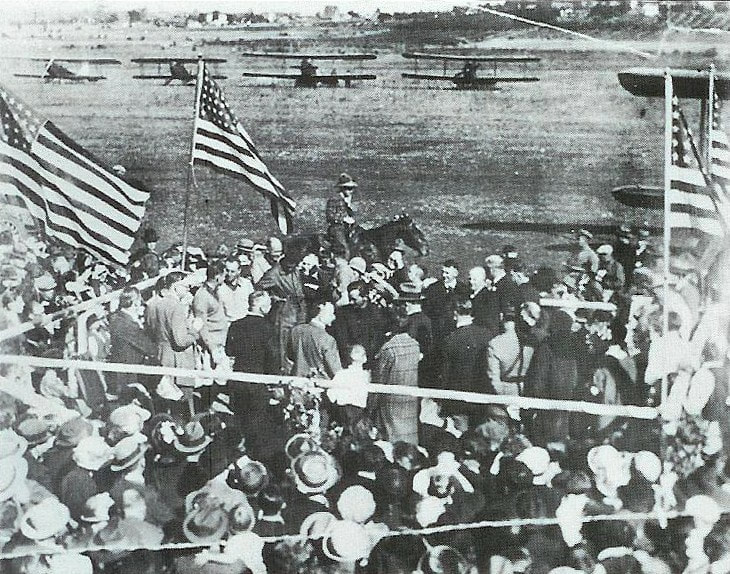

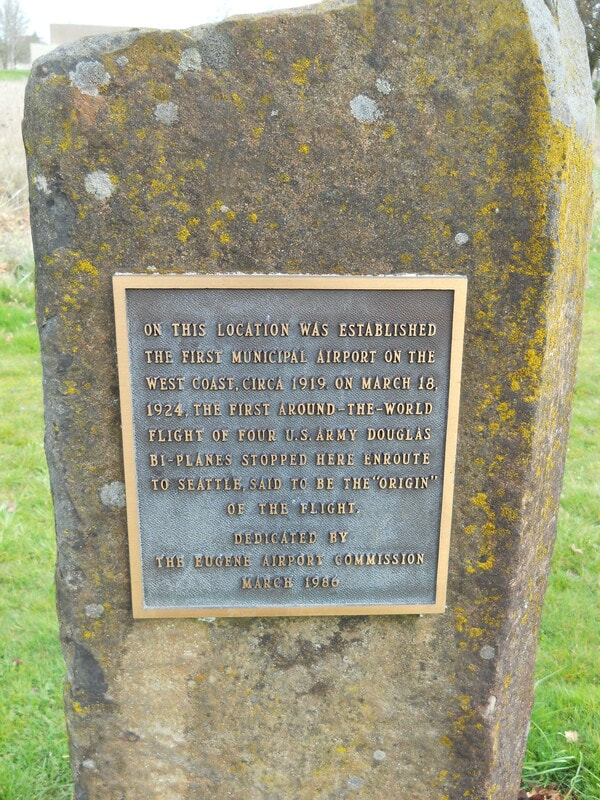

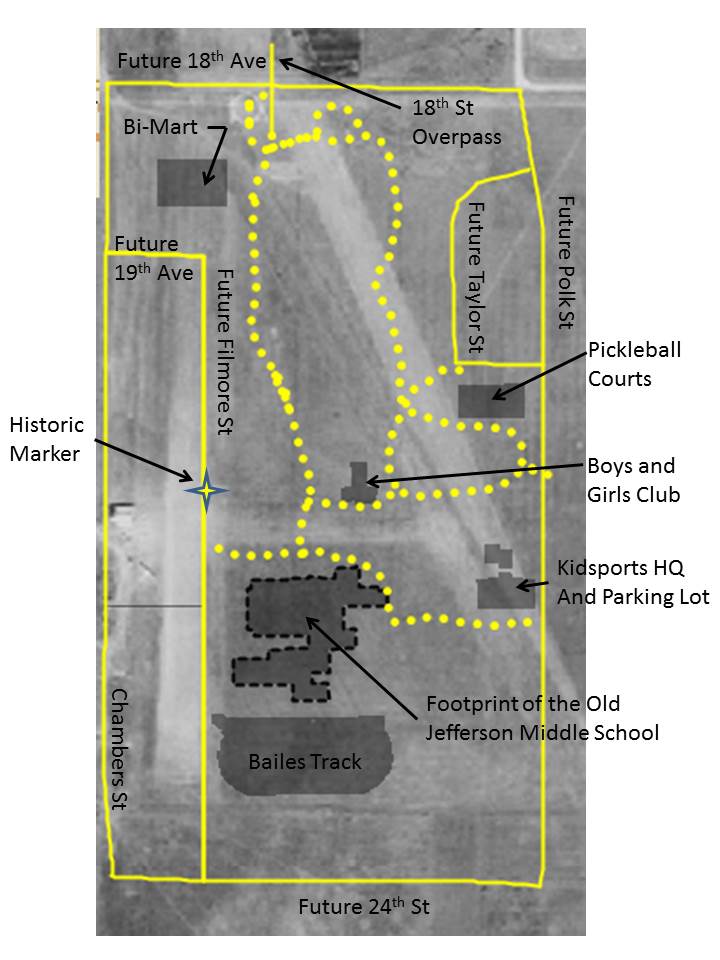

By Gary Arnold First called the Chambers Street Airport, then the Eugene Airfield/Airport, and finally the Eugene Airpark (some wags even called it cow pasture field) the facility operated until 1955. I prefer using the term "airfield" because the runways were never paved and few site improvements were ever made. Even though pretty primitive by today's standards, and located in a relatively rural part of the state, the Eugene Airfield was site to a surprising number of interesting events. Mahlon Sweet (yes, the person our current airport is named after) was named to the Eugene Chamber of Commerce Aviation Committee. Under his leadership, the City opened an airfield in 1919 in what is now Westmoreland Park. The Eugene Airfield was the very first municipal and non-military airfield to be built on the entire west coast. Bear in mind, the Wright brothers had just flown in 1903 in a plane that could only hop 120 feet from take-off to touchdown. Only 16 years later the concept of city-to-city flights was becoming a reality. And Eugene wanted to be part of that reality. With the field in operation, the first Eugene Airshow happened on July 4th, 1919. It seems to have had only one pilot (Lt. James Krull), but he put on an exciting show of aerobatics with the notable "trick" of a high speed "buzzing" low over Willamette Street. For many people this was the first time they had ever seen an airplane. Although a non-military field, about a year after its opening, the US Army stationed a squadron of flyers in Eugene to fly over the vast forests in the area to spot fires. Back then the Army was responsible for protecting National Parks, and the fledgling National Forests and the involvement of the military in civic matters was not that unusual. An interesting note about the fliers, the commanding officer of the detachment was Maj. H.H. “Hap” Arnold. [Authors Note-I don't believe him to be a relative.] Hap Arnold went on to command the entire Army Air Corp in WWII. He was then named the first commander of the US Air Force, when it became a separate branch of the military. He is the only person to be of 5-Star rank (the highest rank possible in the military) in two services. Near the end of the war, Hap was known to have come back to Eugene and spent a week fishing with Mahlon Sweet up on the McKenzie River. A 1925 map of the field shows that directly south of the hangers there was a trap shooting club, with three shooting positions. Words fail to express how different an age 1924 was. Eugene Airfield had encounters with not just one, but two aircraft that are now on display in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum on the mall in Washington DC. Douglas World Cruiser The United States Army wanted to attempt an audacious feat. They placed an order with the Douglas Aircraft Company of Santa Monica, CA, for an aircraft that would be capable of flying around the world. The company built four aircraft which first flew in November of 1923 (just under 20 years after the Wright brothers). The aircraft were named after cities—Boston, Chicago, New Orleans, and Seattle. The planes could be fitted with wheels or floats for water landings. Both would be used on the trip. The long-range flying over large tracts of uninhabited land and open ocean would only be possible with extensive support by the US Military. A huge logistical system of supplies, gasoline, and spare parts provided by the Army and Coast Guard was placed along the route. The four Cruisers were flown north from the factory to Seattle, the official beginning and end of the around-the-world flight. The planes landed at the Eugene Airfield for a re-fueling stop on their way north. The official attempt began on April 6, 1924 when the four planes left Sand Point Airfield and flew north to Alaska. Within a few weeks, the Seattle crashed and the expedition was down to three planes. The remaining planes made it across Asia and Europe until the Boston landed hard in the Atlantic Ocean near the Faroe Islands and was declared a total loss. Chicago and New Orleans continued west across the Atlantic where they were joined by a new aircraft in Nova Scotia, the Boston II. The threesome then flew across eastern Canada and the United States, landing back in Eugene on September 27, 1924. The official end of the expedition was the next day in Seattle. The "official" route covered 23,942 nm (44,342 km). Time in flight was 371 hours, 11 minutes, and average speed was 70 miles per hour. Unofficially, note the fact that these planes had already landed in Eugene on their way up to Seattle. It is completely historically true to say the the first around-the-world flight first went from Eugene to Eugene, not from Seattle to Seattle. Pictured below is a welcoming ceremony for the returning fliers and planes on September 27, 1924. Thousands from Eugene attended. Oregon Governor Walter Pierce was on hand to greet the fliers (I believe he is the man standing at the railing, next to the child). The Cruiser Chicago is currently on display in the Smithsonian. Ryan Spirit of St. Louis and Charles Lindbergh Most everyone has heard of Charles Lindbergh. When he completed his solo non-stop crossing of the Atlantic in May of 1927, he became the most famous man in America. The "Lone Eagle" was in great demand for speeches and business opportunities, but Harry Guggenheim was able to entice Lindbergh to embark on a three-month tour of the United States from July through October of 1927. Their mutual goal was to promote aviation to the public. Flying in the Spirit of St. Louis, Lindbergh landed in 48 states, visited 92 cities, and gave 147 speeches. Although he didn't land, he flew directly over the Eugene Airfield on September 16, 1927. Thousands knew he was coming and turned out to see Lindbergh fly low over the field and perform stunts over downtown Eugene and Willamette Street. The picture below was taken at the Oakland, California, airport, the day after flying over Eugene. The Spirit of St. Louis is currently displayed in the great entrance hall of the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. One of the truly great aircraft in American history. As time passed, airplanes developed higher performance which required runways that were longer and that were paved. The city grew outward until the Airfield was surrounded on all sides by homes. A petition to close the Airfield, by now called the Eugene Airpark, was circulated in 1954 citing noise and safety concerns. In the city election of November 1954, the measure to close the facility passed, and it closed down for good the the next year. A plaque was put up in 1986 near where the hangers were, but one finds few other physical signs that this urban setting was once the location of an airport. Descriptions of where the Eugene Airfield was have been universally vague. Although generally right, they were not useful in picturing its exact location. The map at the left furnishes modern-day landmarks placed on an aerial photo from the mid-1930's. The dotted yellow lines are walking and bike paths within Westmoreland Park. The map on the right has these modern-day landmarks removed. Notable is how few of our modern streets existed back then, in fact Chambers Street was the only way to get to the Airfield. I like to picture a take-off run in an old bi-wing airplane that requires taxiing north from the hangers, through the Bi-Mart store, hanging a right at the south end of the 18th Avenue overpass, and then gunning the engine to try and get to take-off speed (around 80 MPH) before hitting the Kidsport building. Not to mention avoiding the trees and landscaping berms that have been added since 1955. Yet if you stand at the south end of the overpass and look towards Kidsport and squint just right, you can still almost see the runway and maybe even hear the sound of aircraft engines. Sources and Further Reading

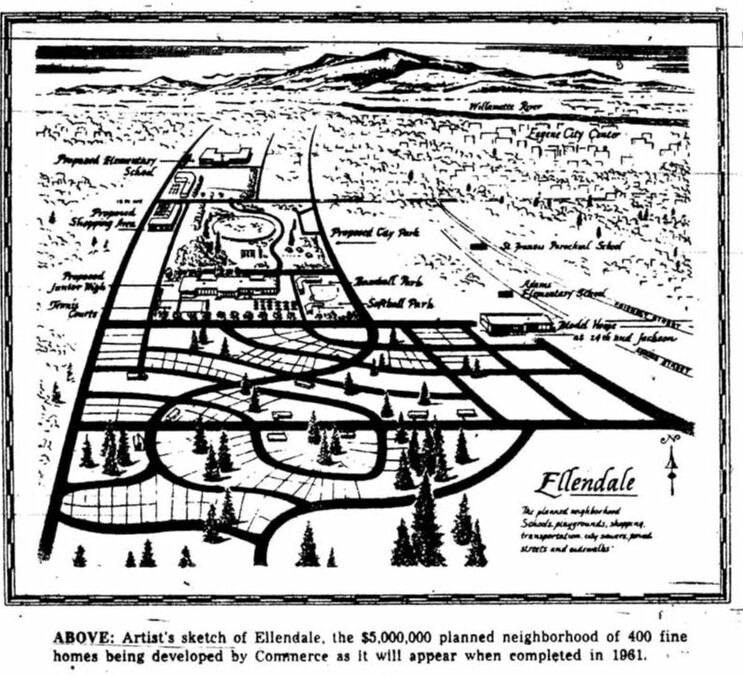

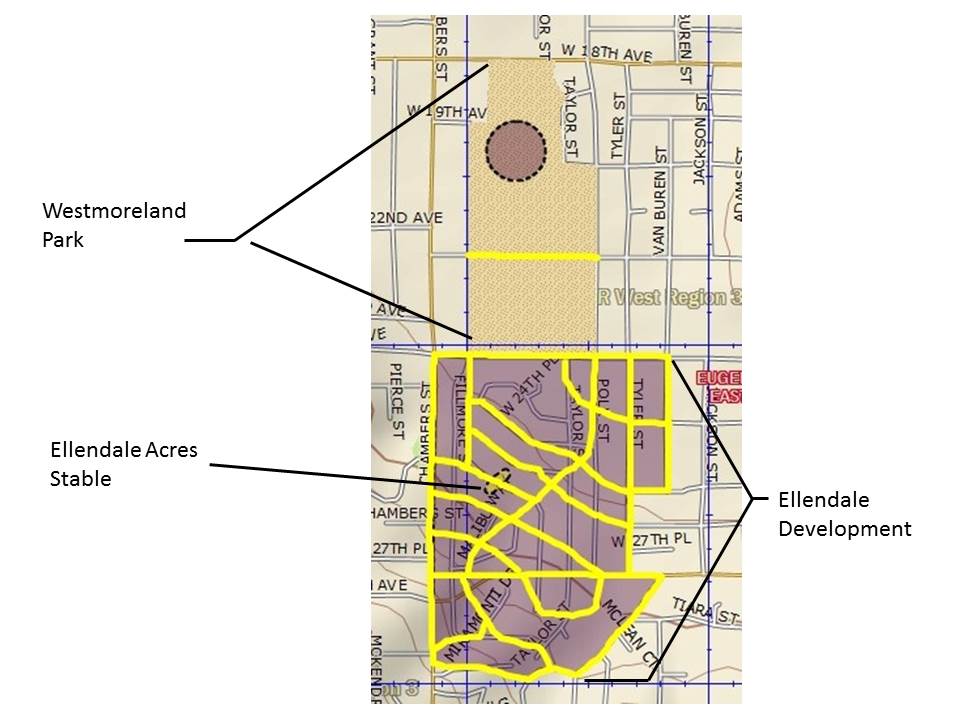

A portion of the Friendly Neighborhood owes its origins to a ten-phase housing development called Ellendale. This land was owned by a woman named Georgia Ellen Dale. She is known to have operated a show horse stable named Ellendale Acres from approximately 1950 to 1955 at 26th Avenue & Chambers Street. The original Ellendale development (1955) was followed by nine Ellendale additions. Around 250 total lots were created.  The original development consisted primarily of a modern, tract house built using mid-century post and beam construction. About fifty of these houses were built in Ellendale. An additional three are located in the nearby Adamsdale development. The need for post WWII housing resulted in plans for thousands of new developments across the country. Most never got off the ground. The somewhat fanciful 1955 artist's rendition shown above would never have fit onto the local topography. The map below compares the artist's concept for street alignments (shown in yellow) to what the street alignments came to be (shown in white). The approximate location of Georgia Ellen Dale's riding stable is also noted. The 1955 sketch also shows Westmoreland Park bisected into two parts by 22nd Avenue and some kind of pond to the west of Taylor Street, just south of 18th Avenue.

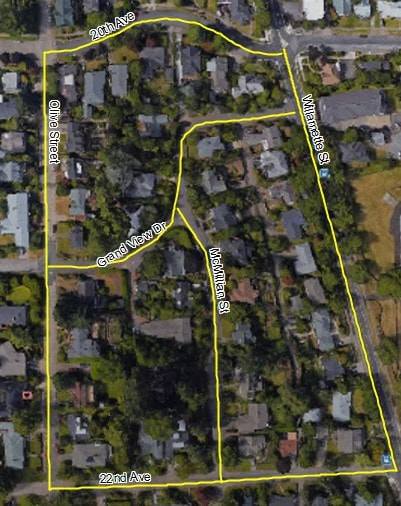

Across from the site of the old Civic Stadium, a pair of concrete steps leads up from Willamette Street to the sidewalk. This is one of the few physical remains of the former Eugene General/Mercy Hospital. A few houses north of here, a second set of steps to the hospital have been re-purposed for access to a residence. Built in 1906 by a group of doctors and businessmen, the hospital was opened as Eugene General. By 1912, the hospital was having hard financial times, and was sold to the Catholic Sisters of Mercy. They renamed the facility Mercy Hospital and opened a nursing school. At the time of the purchase, the Sisters placed an ad in the local Polk's Directory: "The building is situated on College Hill commanding a beautiful view of the City and surrounding country. The location is most sanitary and healthful, the slight elevation affording the best of drainage and atmospheric conditions. Though but a few minutes walk from the center of town and conveniently reached by the College Hill Car Line, the Hospital is entirely outside of the noise and dirt of the city." Indeed, a photo from 1910 shows that except for a few houses, the hospital is the only building standing on College Hill. In 1928, the Sisters outgrew the Mercy Hospital site and moved to Pacific Christian Hospital (which evolved into Sacred Heart Medical Center and ultimately Riverbend Hospital). The hospital buildings sat deserted until being razed in 1940. So where exactly were the hospital buildings? The image on the right shows the positions of the hospital building footprints (yellow), old road alignments (white) and the stairways from Willamette Street (green) superimposed on an aerial photo from around 2010. Those positions were established from a mid-1930's aerial photo. The image on the left is the same aerial photo with current street alignments labeled.

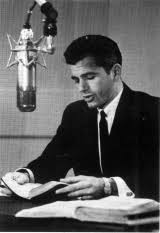

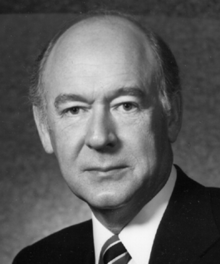

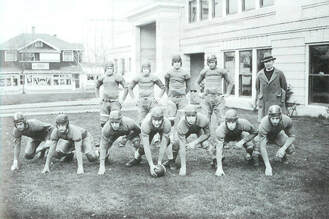

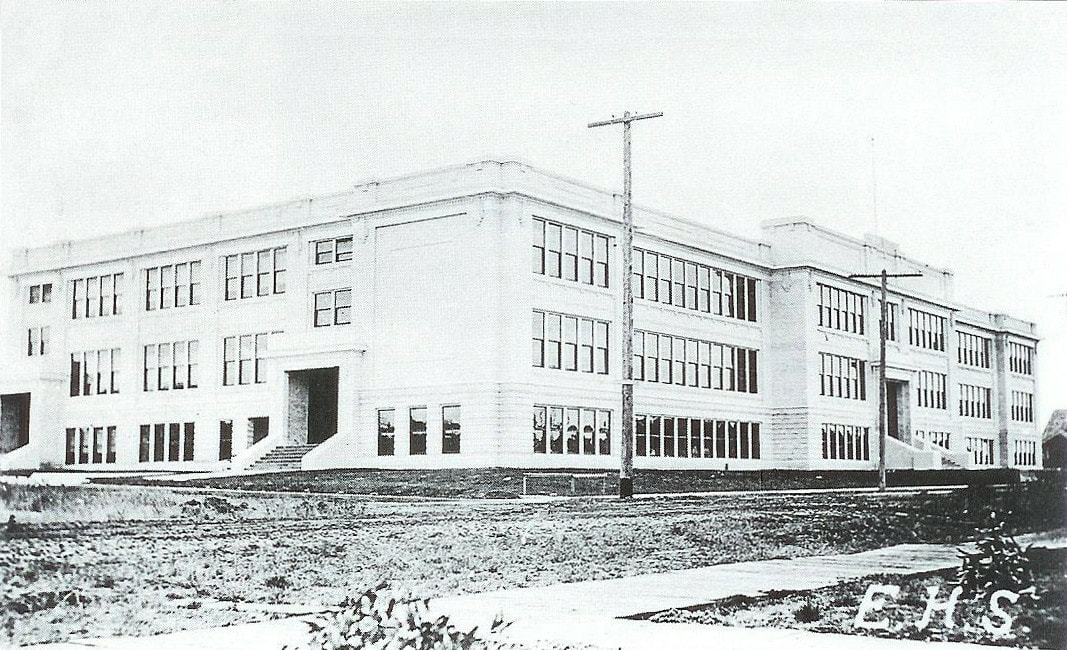

Newly constructed (1915) Eugene High School looking towards the main entrance from the corner of 17th Avenue and Charnelton Street. The school took up the entire block (bounded by 17th Avenue, Charnelton Street, 18th Avenue and Lincoln Street). The three-story brick building was finished in plaster. Note the wooden sidewalks in the foreground. This building replaced the first Eugene High School located at the southwest corner of 11th Avenue and Willamette Street. Although technically across the street from the FAN northern boundary, the school educated many students that lived in the Friendly neighborhood.  Famous Alumni Paul Simon (1928-2003) Lieutenant Governor of Illinois 1969-1973 Congressman from Illinois' 22nd District 1975-1985 United States Senator from Illinois 1985-1997 Born in Eugene, Paul's family moved to Portland before he graduated from Eugene High School. He would have been in the the class of 1945.  Garner Ted Armstrong (1930-2003) Minister, Author, Educator, Radio and Television Commentator Class of 1947  Cecil Andrus (1931-2017) Governor of Idaho (1st Term) 1971-1977 United States Secretary of the Interior 1977-1981 Governor of Idaho (2nd Term) 1987-1995 Class of 1948 Sports Championships Eugene High School won two state basketball championships (1927, 1946). It played in state title games nine times. Boys Basketball Boys Baseball Boys Golf Eugene High School became Woodrow Wilson Junior High School in 1952, when a new high school was built at 400 East 19th Avenue. The main building was razed in 1973. (photos courtesy of the Lane County History Museum)  The detached, former gymnasium (shown above at left) still stands on the southeast corner of the site. It has been modified to include a Mansard-type roof form. The Lighthouse Temple currently occupies the property. Compiled by Natalie Perrin By 1937 in Eugene, Oregon, there was a growing need for an athletic field, both for the community and the schools. On December 3rd, 1937, the Eugene Register-Guard printed the first article referencing the "Big Amazon Park Project." By December 8th, 1937, a committee had been formed by the Eugene Chamber of Commerce and plans were being formulated for a new athletic field to be built through the cooperation of the Chamber Committee, the Eugene Public School Board, and the Eugene City Council. By December 24th, 1937, the WPA was reported to be interested in the development and building of the recreation center. On January 11, 1938, the Register-Guard presented the facts regarding the financial plans for the new athletic field. The city council was asked to turn over the land known as the Amazon tract, which was held for $6000 in back taxes. The school board was asked to contribute $6000, and the committee guaranteed to raise another $6000 so the first year work could be completed. The WPA was set to contribute the labor. The $12,000 contributed by the school board and the committee would be enough to grade the field and build the covered grandstand, which would seat 4,000 people. On January 26, 1938, the Register-Guard reported that the "Park Project is Threatened by Deadlock." The concern of who would pay the $6000 in back tax assessments, the city or the school board, seemed to spell the end of the project. Without the deed from the city, the school board was concerned that they would not be able to secure the WPA for the project. The controversy lasted months, until it was decided to put the vote to the community at large. On Friday, May 20th, 1938, Eugene citizens went to the polls to vote on the issue to levy a one-half mill tax ($0.50 per $1000 of assessed property value) to repay the debt of $6000 in outstanding liens to the property. Voters approved the project by an almost 2-1 margin, enabling the proposed athletic field to move forward. The title to the Amazon tract was deeded over to Eugene Public School District 4J on June 13th, 1938 to "be used as a recreation area for the School District and for the municipality." Eugene Civic Stadium would never have been constructed without the display of outstanding public support it received and the cooperation of the numerous civic agencies involved. This unique cohesion of community development and city planning illustrates the camaraderie apparent in WPA projects built throughout the country during the Depression-era. The stadium meets Criterion A for its distinctive characteristics of community planning and development, which brought the government and community together during these difficult times. On May 15, 1938, just prior to the special election, the Eugene Register-Guard presented a plan to the public for the proposed development of the Amazon tract area. The proposed site would include a football and baseball field and grandstand, track field, swimming pool, tennis courts, shuffle board and Ping-Pong courts. The plan was to begin on the football and baseball field first, with the other areas being developed later. Work began on June 21, 1938, with Jay F. Oldham contracted for the grading of the land. Graham Smith, a local of Eugene, was named architect for the grandstand, the plans of which were approved in July. Smith, along with the manpower of the WPA, utilized local old growth Douglas fir exclusively in the construction of the grandstand. The work was completed in mid-September, and a dedication ceremony featuring the Eugene High School marching band was held on October 22, 1938.  Eugene High School Football Team, circa 1930. Current site of the Cornucopia Restaurant (in background). Eugene High School Football Team, circa 1930. Current site of the Cornucopia Restaurant (in background).Photo Courtesy of the Lane County History Museum. The first event at Civic Stadium, the annual rivalry football match between Eugene High and Corvallis High, was held on October 28, 1938. The grandstand still did not have a roof, and both players and fans were rain-soaked by the end of the game. The match, played on the clay and sawdust field, ended in a 0-0 tie. By the 1939 football season, floodlights and the grandstand roof had been erected at Civic Stadium. The roof was designed by the West Coast Lumberman's Association of Seattle, Washington, and utilizes the same local, old growth Douglas fir that can be found in the grandstand construction. Plans for the other parts of the athletic complex never materialized and the land was developed into South Eugene High School.  Eugene High School Football Game, November 11, 1953 Eugene High School Football Game, November 11, 1953 During the period of significance (1938 - 1955), Eugene Civic Stadium was primarily home to high school football, baseball, and soccer games. The stadium was designed as a multi-use facility, and converted easily for various types of sporting events. Eugene Civic Stadium has been home to numerous high school ball games, graduations, 4th of July celebrations and even rodeos throughout the years. In 1941 the School District added the Heating Plant, a small ancillary building with an 880 gallon water tank, to the site. The Heating Plant initially acted as the sole source for hot water at the stadium, and serviced the locker and bath rooms by utilizing sawdust to run the boiler. The building, through structurally unaltered, has not served its initial function since the water tank was removed, and today is utilized as a storage facility for the site. In 1946 the School District added the Garage and Living Quarters, which functioned on the ground level as a repair garage for the Bus Depot that, at that time, was located in what is now the parking area. With the stadium operating both Saturday night and Sunday afternoon for hardball games and at least twice a week for softball, the groundskeeper was on duty 24 hours per day. Recognizing that this was a full time job, the School District of the time built two apartments above the garage for the Groundskeeper and his family. The initial groundskeeper was William "Grady" Lewis, who was a WPA foreman for the Eugene Civic Stadium project. When the stadium was completed he was asked to stay on and run the facility. Mr. Lewis' son, Graydon Lewis, who is still living in Eugene, remembers life as a boy at Civic. Living in a nearby house prior to the construction of the Garage and Living Quarters, Mr. Lewis assisted his mother and father by helping to clean the stadium on Sunday mornings while his father drug and marked the sand field. Mr. Lewis remembers the stadium as a playground for himself and his friends, and knew everything under the grandstand including places to find change dropped during the games. Though Mr. Lewis, the younger, never lived in the Garage and Living Quarters (he joined the Navy at this time), he remembers it as "a fine apartment" for his family. Sometime in 1950 - 55, the Maintenance Office was constructed. This building acted as a storage facility for equipment needed to grade and paint the field. The building served as an office and maintenance building for the groundskeeper, as well as the player's lounge.  In 1969, Civic Stadium became home to Eugene's own minor league baseball team, the Emeralds. Upgraded to the Class AAA Pacific Coast League, the Eugene Emeralds required a larger facility than they currently had, and sought the assistance of the Eugene School District when plans to build a new stadium were unsuccessful. Baseball had not been played at Civic Stadium in over twenty years, but the team was granted a three-year lease to use and improve the stadium. It was in 1969 that the stadium was updated, converting it from its almost full-time status as a football stadium into a baseball facility. Two large light standards and 800 wooden, theatre-style box seats were purchased from the soon to be demolished River Island Stadium, which had been home to the San Diego Padres minor league team since 1936. The light standards were added to the roof of the Grandstand, and the box seats were placed on risers in front of the original stands to allow for additional seating.  The press box was relocated at this time as well, having originally been located on the Grandstand roof. A new press box was built into the seating, in the curve of the L-shaped Grandstand, and is clad in vertical wooden board-and-batten siding. The field was updated and the concession area paved. Other improvements ranged from new paint to new fencing. A metal, hand-turned score board was installed, which added to the character of the park. The wooden risers were replaced in 1986 by the current blue plastic risers, due to the accelerated rot and deterioration that had occurred in their exposed, uncovered placement. Additional improvements have been made over the years including adding sprinklers and bringing the site up to the standards of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). However, in spite of continued improvements, Eugene Civic Stadium retained integrity of location, setting, materials, design, workmanship, feeling and association. The Eugene Emeralds are ranked as one of the most popular teams of the Northwest League, having drawn no less than 100,000 fans per year since 1985. As of opening day 2008, Eugene Civic Stadium was the 9th Oldest Minor League Ballpark in the United States. It was the third oldest minor league stadium in use west of the Rocky Mountains. Civic Stadium was a place where the community enjoyed America's favorite pastime every summer, and is a part of Eugene's history. Continuously used as a municipal athletic facility since its inception, Eugene Civic Stadium met National Register Criterion A for its initial and continued contribution to the entertainment and recreational needs of Eugene and the surrounding communities in the Pacific Northwest. Civic Stadium Timeline:

Early Owl Farm- Tessa & Jake McCusker (and their twin boys) are the farmers behind Early Owl Farm, a small family farm specializing in seasonal vegetables and fruits, eggs from pastured hens and beautiful cut flowers. The McCusker’s utilize an approach called "regenerative farming" which goes beyond the scope of "organic" and results in a thriving soil food web, increased carbon sequestration, nutrient-dense food and an improved farm ecosystem. They minimize tilling the soil as much as possible, plant diverse cover crops to feed the soil and pollinators, compost intensively, house their hens in a mobile chicken house so they can access fresh pasture every few days, and maintain large areas of native flowers, shrubs and trees to aid the local fauna. Please stop by to chat, and get to know these wonderful local farmers!

Contact: Website- www.earlyowlfarm.com/, Facebook and Instagram pages will keep you in the loop of farm happenings. You can find their market stand at the following spots: Early Owl Farm Stand (Sundays 10am-2pm starting in early May), Spencer Creek Growers Market (Saturdays 10am-2pm starting mid-May) and Amazon Farmers Market (Thursdays, 11am-4pm starting in June). Friendly Fruit Tree Project-Matt Lutter (Friendly neighbor and former FAN Board Member) spearheads The Friendly Fruit Tree Project, an all-volunteer effort to build relationships between fruit-loving Friendly neighbors and fruit tree owners (or stewards) who might have more fruit than they can handle. When a fruit owner offers to share their fruit with the Friendly Fruit Tree Project, a volunteer Harvest Leader "adopts" the site and coordinates the event for the steward and harvesters. Harvested fruit is split roughly into thirds between volunteers, the steward, and those in need. Contact: FB The Friendly Fruit Tree Project phone: (541) 632-3260 (S)Beyond Toxics (BT) - Lisa Arkin (Executive Director BT, Friendly neighbor and former FAN Board Member) will be sharing information from studies recently published by the Center for Food Safety which found high levels of pesticide residues in the kinds of fruits and vegetables we may grow in our gardens. Foods like apples and spinach can absorb chemicals that cannot be washed off. Beyond Toxics challenges environmental pollution by taking on its root causes and working for lasting change. BT activates and organizes the people most affected by overburdens of pollution and harm. Their goal is to build a statewide environmental justice movement to advance the power of Oregonians on the frontlines of disparities in health, wealth and work. Contact: email- [email protected] phone- 541-465-8860 (S)Walama Restoration Project- Walama Restoration will give a short presentation on “The Walama Restoration Project (WRP), a community organized non-profit, founded in 2001, dedicated to environmental stewardship and biological diversity through education and habitat restoration." Kris will be focusing on "sustainable yards". Contact: web- www.walamarestoration.org email: [email protected] phone: 541-484-3939 350 Eugene- The local Eugene Chapter of 350.org will be present to talk about their series of local workshops designed to educate on ways we can all improve sustainability and answer your questions on how you can get involved in the Drawdown Eugene campaign that advocates for the successful planning, completion and adoption of the City of Eugene’s Climate Action Plan 2 (CAP 2). (S)Urban Bees- Honey Bee Jen (bee keeper, Friendly neighbor) - Jen Hornaday, the owner of Healthy Bees = Healthy Gardens, will be speaking on ways we can protect our precious pollinators. Jen’s comments will focus on creating healthy spaces for honey bees and how to invite pollinators into your yards to increase your fruit, flower, and vegetable production. After her presentation, stop by Honey Bee Jen’s booth for a healthy honey tasting and to learn more about Honey Bee preservation efforts in the Eugene area. Jen will also have honey, pollinator seeds, propolis, and bee gifts for sale. (S)Common Ground Garden (CGG)- Teresa Siemanowski (Friendly Neighbor) will give a short presentation on how a group of FAN neighbors worked together to form a community garden that benefits all. Common Ground Garden, which today is a beautiful and productive neighborhood food sharing garden located at 21st and Van Buren Street, began in 2009 with a City of Eugene neighborhood matching grant and a team of dedicated volunteers committed to transforming gravel into an oasis of organic, bee friendly, sustainable, collaborative food production. CGG meets every Saturday from 10-12 for a family friendly work party to garden and connect with neighbors and friends. Garden tools and gloves are provided, and everyone is welcome! Contact: FB Common Ground Garden email: [email protected] ToolBox Project- The ToolBox Project is a volunteer-driven tool-lending library open to residents of Lane County, Oregon. They share home and garden tools with our community so we can all build and grow together. Come find out how you can become a member, how you can donate tools, and/or become a sponsor. Contact: web www.eugenetoolboxproject phone: 541-838-0125 email: [email protected] Lane County Master Gardeners (LCMG) - Jan Gano (President LCMG) will be present to answer questions about Oregon State University’s Master Gardner Program. The Oregon State University Extension Service provides Oregon volunteers with research-based knowledge and education that strengthens communities and economies, helps sustain natural resources, and promotes healthy families and individuals. Trained Master Gardener volunteers help educate and advise other home gardeners in our community. Many people new to Lane County as well as inexperienced gardeners are interested in obtaining local gardening advice. The Master Gardeners program focuses on topics such as diagnosing plant and insect problems, preparing soil for planting, identifying plants, and selecting ornamentals and varieties. Contact: web: extension.oregonstate.edu/mg/lane phone: 541-344-0265 email: [email protected] FAN Team Tables- Please go to FAN website www.friendlyareaneighbors.org Get Involved, to get contact information

|

AuthorFriendly Area Neighbors Archives

June 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed