|

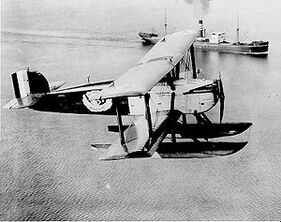

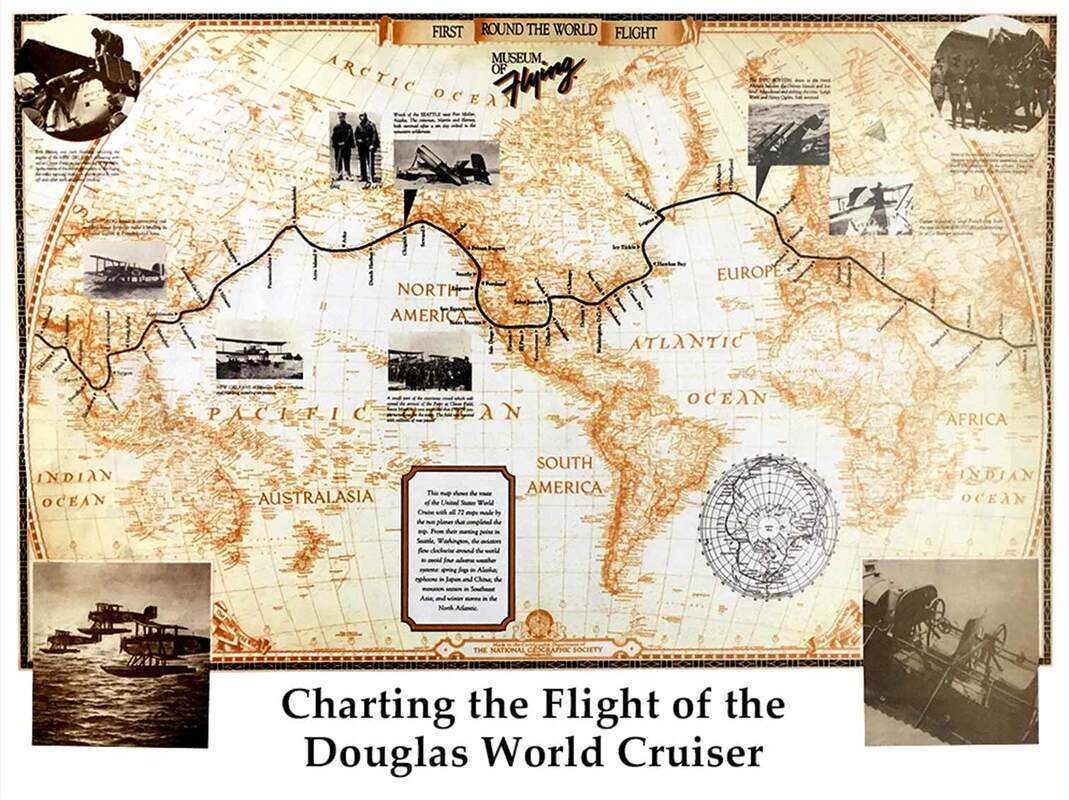

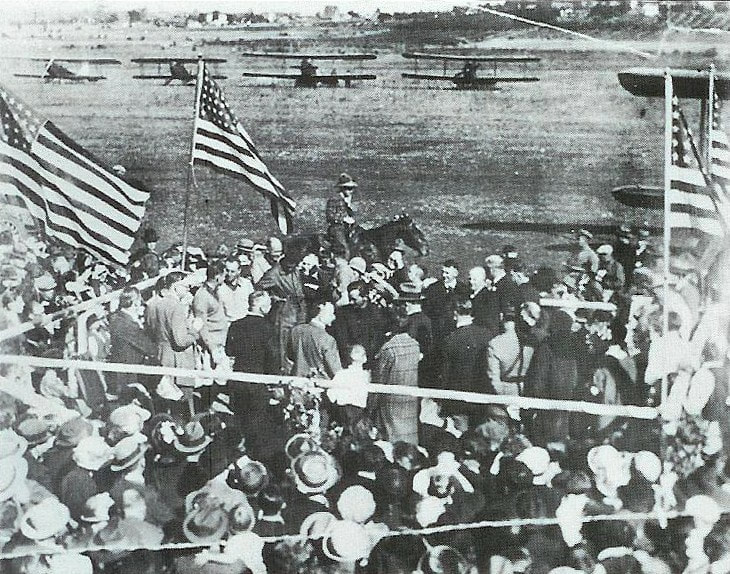

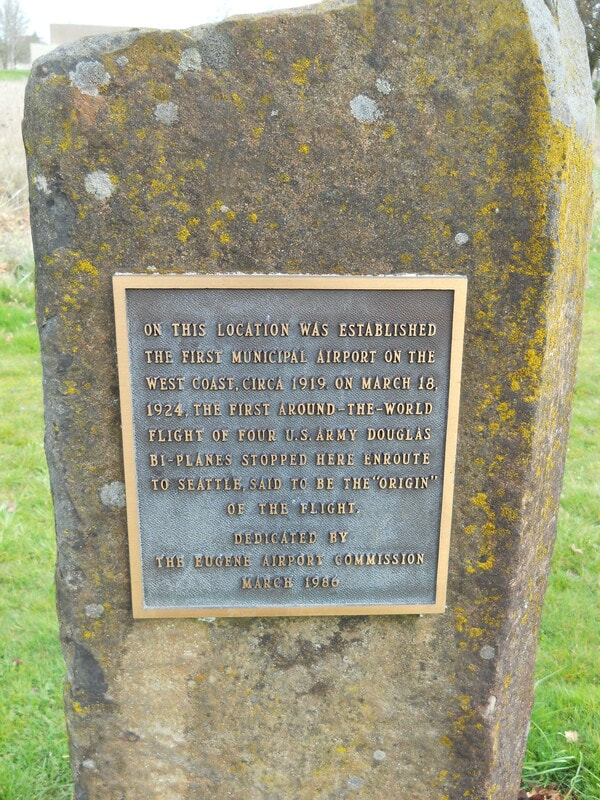

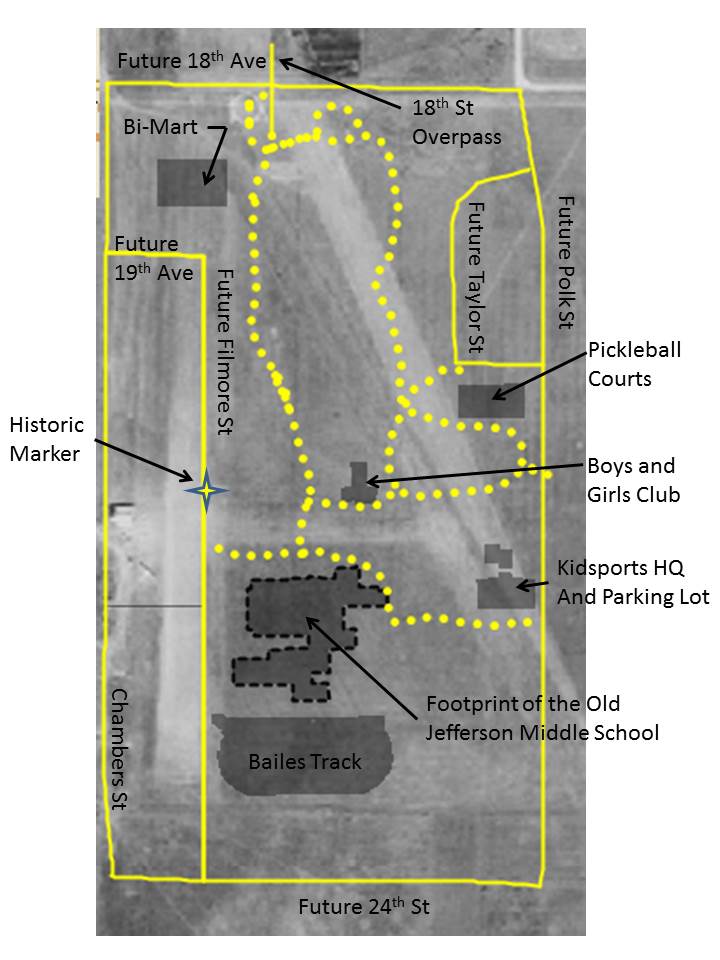

By Gary Arnold First called the Chambers Street Airport, then the Eugene Airfield/Airport, and finally the Eugene Airpark (some wags even called it cow pasture field) the facility operated until 1955. I prefer using the term "airfield" because the runways were never paved and few site improvements were ever made. Even though pretty primitive by today's standards, and located in a relatively rural part of the state, the Eugene Airfield was site to a surprising number of interesting events. Mahlon Sweet (yes, the person our current airport is named after) was named to the Eugene Chamber of Commerce Aviation Committee. Under his leadership, the City opened an airfield in 1919 in what is now Westmoreland Park. The Eugene Airfield was the very first municipal and non-military airfield to be built on the entire west coast. Bear in mind, the Wright brothers had just flown in 1903 in a plane that could only hop 120 feet from take-off to touchdown. Only 16 years later the concept of city-to-city flights was becoming a reality. And Eugene wanted to be part of that reality. With the field in operation, the first Eugene Airshow happened on July 4th, 1919. It seems to have had only one pilot (Lt. James Krull), but he put on an exciting show of aerobatics with the notable "trick" of a high speed "buzzing" low over Willamette Street. For many people this was the first time they had ever seen an airplane. Although a non-military field, about a year after its opening, the US Army stationed a squadron of flyers in Eugene to fly over the vast forests in the area to spot fires. Back then the Army was responsible for protecting National Parks, and the fledgling National Forests and the involvement of the military in civic matters was not that unusual. An interesting note about the fliers, the commanding officer of the detachment was Maj. H.H. “Hap” Arnold. [Authors Note-I don't believe him to be a relative.] Hap Arnold went on to command the entire Army Air Corp in WWII. He was then named the first commander of the US Air Force, when it became a separate branch of the military. He is the only person to be of 5-Star rank (the highest rank possible in the military) in two services. Near the end of the war, Hap was known to have come back to Eugene and spent a week fishing with Mahlon Sweet up on the McKenzie River. A 1925 map of the field shows that directly south of the hangers there was a trap shooting club, with three shooting positions. Words fail to express how different an age 1924 was. Eugene Airfield had encounters with not just one, but two aircraft that are now on display in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum on the mall in Washington DC. Douglas World Cruiser The United States Army wanted to attempt an audacious feat. They placed an order with the Douglas Aircraft Company of Santa Monica, CA, for an aircraft that would be capable of flying around the world. The company built four aircraft which first flew in November of 1923 (just under 20 years after the Wright brothers). The aircraft were named after cities—Boston, Chicago, New Orleans, and Seattle. The planes could be fitted with wheels or floats for water landings. Both would be used on the trip. The long-range flying over large tracts of uninhabited land and open ocean would only be possible with extensive support by the US Military. A huge logistical system of supplies, gasoline, and spare parts provided by the Army and Coast Guard was placed along the route. The four Cruisers were flown north from the factory to Seattle, the official beginning and end of the around-the-world flight. The planes landed at the Eugene Airfield for a re-fueling stop on their way north. The official attempt began on April 6, 1924 when the four planes left Sand Point Airfield and flew north to Alaska. Within a few weeks, the Seattle crashed and the expedition was down to three planes. The remaining planes made it across Asia and Europe until the Boston landed hard in the Atlantic Ocean near the Faroe Islands and was declared a total loss. Chicago and New Orleans continued west across the Atlantic where they were joined by a new aircraft in Nova Scotia, the Boston II. The threesome then flew across eastern Canada and the United States, landing back in Eugene on September 27, 1924. The official end of the expedition was the next day in Seattle. The "official" route covered 23,942 nm (44,342 km). Time in flight was 371 hours, 11 minutes, and average speed was 70 miles per hour. Unofficially, note the fact that these planes had already landed in Eugene on their way up to Seattle. It is completely historically true to say the the first around-the-world flight first went from Eugene to Eugene, not from Seattle to Seattle. Pictured below is a welcoming ceremony for the returning fliers and planes on September 27, 1924. Thousands from Eugene attended. Oregon Governor Walter Pierce was on hand to greet the fliers (I believe he is the man standing at the railing, next to the child). The Cruiser Chicago is currently on display in the Smithsonian. Ryan Spirit of St. Louis and Charles Lindbergh Most everyone has heard of Charles Lindbergh. When he completed his solo non-stop crossing of the Atlantic in May of 1927, he became the most famous man in America. The "Lone Eagle" was in great demand for speeches and business opportunities, but Harry Guggenheim was able to entice Lindbergh to embark on a three-month tour of the United States from July through October of 1927. Their mutual goal was to promote aviation to the public. Flying in the Spirit of St. Louis, Lindbergh landed in 48 states, visited 92 cities, and gave 147 speeches. Although he didn't land, he flew directly over the Eugene Airfield on September 16, 1927. Thousands knew he was coming and turned out to see Lindbergh fly low over the field and perform stunts over downtown Eugene and Willamette Street. The picture below was taken at the Oakland, California, airport, the day after flying over Eugene. The Spirit of St. Louis is currently displayed in the great entrance hall of the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. One of the truly great aircraft in American history. As time passed, airplanes developed higher performance which required runways that were longer and that were paved. The city grew outward until the Airfield was surrounded on all sides by homes. A petition to close the Airfield, by now called the Eugene Airpark, was circulated in 1954 citing noise and safety concerns. In the city election of November 1954, the measure to close the facility passed, and it closed down for good the the next year. A plaque was put up in 1986 near where the hangers were, but one finds few other physical signs that this urban setting was once the location of an airport. Descriptions of where the Eugene Airfield was have been universally vague. Although generally right, they were not useful in picturing its exact location. The map at the left furnishes modern-day landmarks placed on an aerial photo from the mid-1930's. The dotted yellow lines are walking and bike paths within Westmoreland Park. The map on the right has these modern-day landmarks removed. Notable is how few of our modern streets existed back then, in fact Chambers Street was the only way to get to the Airfield. I like to picture a take-off run in an old bi-wing airplane that requires taxiing north from the hangers, through the Bi-Mart store, hanging a right at the south end of the 18th Avenue overpass, and then gunning the engine to try and get to take-off speed (around 80 MPH) before hitting the Kidsport building. Not to mention avoiding the trees and landscaping berms that have been added since 1955. Yet if you stand at the south end of the overpass and look towards Kidsport and squint just right, you can still almost see the runway and maybe even hear the sound of aircraft engines. Sources and Further Reading

Comments are closed.

|

AuthorFriendly Area Neighbors Archives

June 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed