|

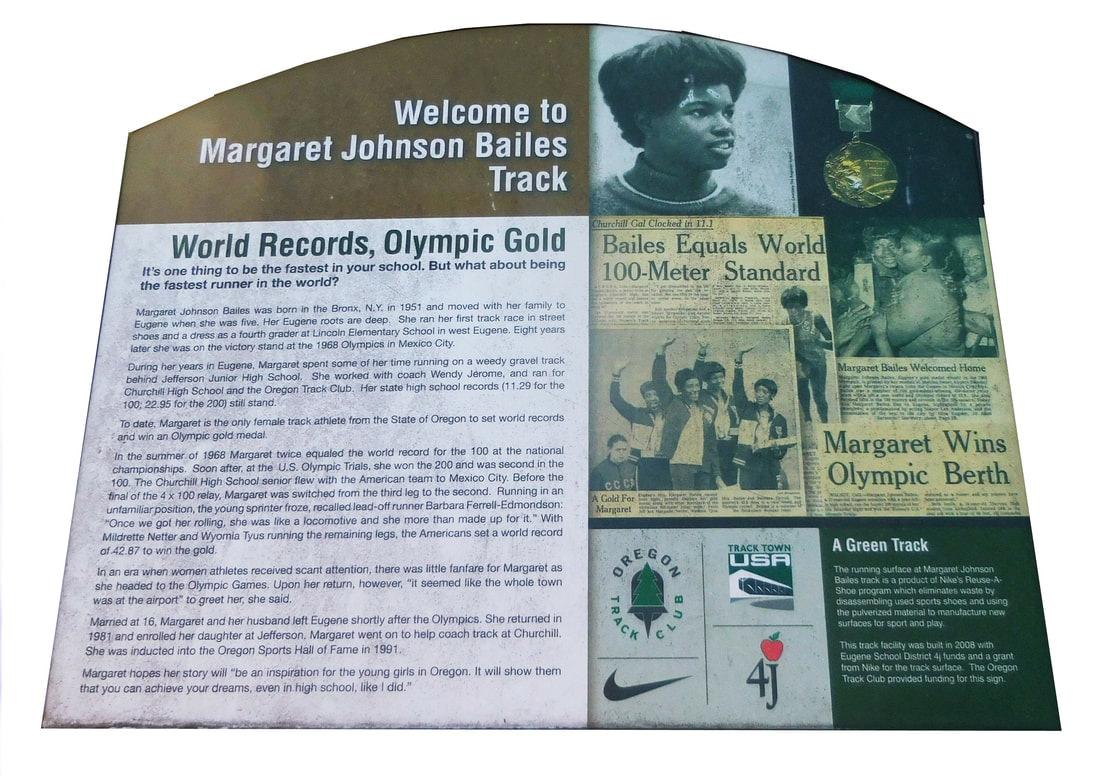

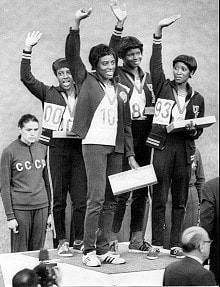

By Gary Arnold If you have ever walked by the track in Westmoreland Park, you may have noticed the plaque. Great athletes deserve recognition, but after all, this is Eugene. Even Olympic level athletes aren't that uncommon. Is there anything to this story that deserves a second glance? Read on, and decide for yourself. Margaret Johnson was born in New York City, in the Bronx. Her father, Duke Johnson, moved the family out to Eugene when she was five years old because he decided Eugene would be a good place to raise his children. A pretty normal kid, she had no particular interest in sports. Just by happenstance, she was passing South Eugene High during an all-comers track meet. On a lark, she entered several events and did pretty well (even though she ran the events in dress shoes). Wendy Jerome was at the meet (wife of world class UO athlete Harry Jerome) and instantly realized that she was watching someone with exceptional talent. Wendy became Margaret's coach and soon ran into a problem. There were no other girls in Eugene that gave her any competition. So she started running against boys—same problem. She eventually was able to find a challenge by giving all her opponents head starts. As she grew older, she started training with some of the sprinters from the UO, and as a high schooler, she usually beat them in practice. At Churchill High School as a junior, Margaret won the 100- and 200-meter races in the state championship meet, and was part of the winning 4 x 100 relay team. That same year she set an American record in the 200 (22.95 seconds) and tied the world record in the 100 (11.1 seconds). As a senior, at the ripe old age of 17, Margaret ran a time of 11.30 seconds for the 100 meters and 22.95 seconds in the 200 meters. Those times were both good enough to win the state championship, in fact, they were both Oregon high school state records. Consider this: 50 years later, these marks still stand as Oregon high school state records. No one sets a track and field record that stands for 50 years. Her times were good enough to qualify her for the 1968 Olympic trials. At the trials she won the 100 and took a second in the 200. While staying in the Mexico City Olympic Village, she contracted pneumonia. She was unable to train for almost a week. Nowhere near full strength, she was able to place fifth in the 100-meter Olympic final (time of 11.3) and seventh in the 200-meter Olympic final (time of 23.1). Margaret had one more Olympic event left, the 4 x 100 relay. Barbara Ferrell would run the first leg, Margaret would run the second leg, Mildrette Netter ran the third, and Wyomia Tyus ran the anchor leg. Wyomia Tyus was the veteran of the group having won two gold medals in the 100 meters and the 4 x 100 relay four years earlier in the Tokyo Olympics. She had just won another gold medal in the Mexico City 100 meters, setting a new world record. Barbara Ferrell, in that same race, had taken the silver medal. The US fielded a strong team, but there were plenty of good sprinters competing. And several of the national teams had a lot more experience working together as relay teams. Poland was one of the favorites coming into the event, but they had dropped the baton in the qualifying heat and were out. You can watch the entire race. This is a classic sports film, and well worth watching, but the womens 4 x 100 begins at time 1:28:00 and runs through about 1:30:00. The US team did win in a time of 42.88, setting a new world record. But consider this: the first seven teams across the finish line also broke the previous world record. Imagine running a race where you run faster than anyone else ever has, and coming in seventh! The US team didn't break the record, they smashed it. The world record would stand until the Munich Olympics, four years later. And then came what is perhaps the most amazing part of the story. In today's world of woman's Title 9 access to sports scholarships, the pro track circuit and corporate shoe endorsements, it is difficult to remember a time when opportunities in sports were limited, especially to women and especially to women of color. After the Olympics, Margaret walked away from the world of sports and never competed again. By the time she was 17, she had married, had a daughter, and had moved to California. Years went by, and only family and Margaret's closest friends even knew of her accomplishments. But the record books had not forgotten her, and eventually a new generation of track fans began to discover the story.

Margaret was inducted into the Oregon Sports Hall of Fame and the High School Track and Field Hall of Fame. She was invited to attend the 2008 Olympic Trials in Eugene as an honored guest. And the next year, the old Jefferson Middle School cinder track where Margaret used to train was re-built into a modern all-weather facility and dedicated as the Margaret Johnson Bailes Memorial Track. More Information Comments are closed.

|

AuthorFriendly Area Neighbors Archives

June 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed